[ad_1]

What they’ve learned so far can help us prepare.

Sonja Skelly is Director of Education for the Cornell Botanic Gardens and an Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Department of Horticulture there. She gave me a virtual tour of Cornell’s Climate Change Demonstration Garden, and some of the takeaways from their work so far that we can use to make our own gardens more resilient in the face of a shifting landscape.

Read along as you listen to the Sept. 12, 2022 edition of my public-radio show and podcast using the player below. You can subscribe to all future editions on Apple Podcasts (iTunes) or Spotify or Stitcher (and browse my archive of podcasts here).

a garden to face a changing climate, with sonja skelly

Margaret Roach: I’m so glad that you could take the time out during back-to-school peak season to talk about this.

Sonja Skelly: Oh, thank you so much for having me. It’s such an honor to be here.

Margaret: I cannot believe that I did not know about this work. I felt almost embarrassed when I discovered it, thanks to one of your colleagues who turned me on to the website and so forth. And so I’ve been reading a lot about what you’ve been doing.

And the way the Climate Change Demonstration Garden—which we should say is just one small part of this incredible Botanic Garden at Cornell—but the way it’s set up is deceptively simple. But wow, it’s also so revealing about what’s going on outside and what will continue to be going on as the planet continues to warm. So tell us a little bit about it, sort of set the scene. Give us a visual of the layout of the garden, and what it’s meant to help us understand.

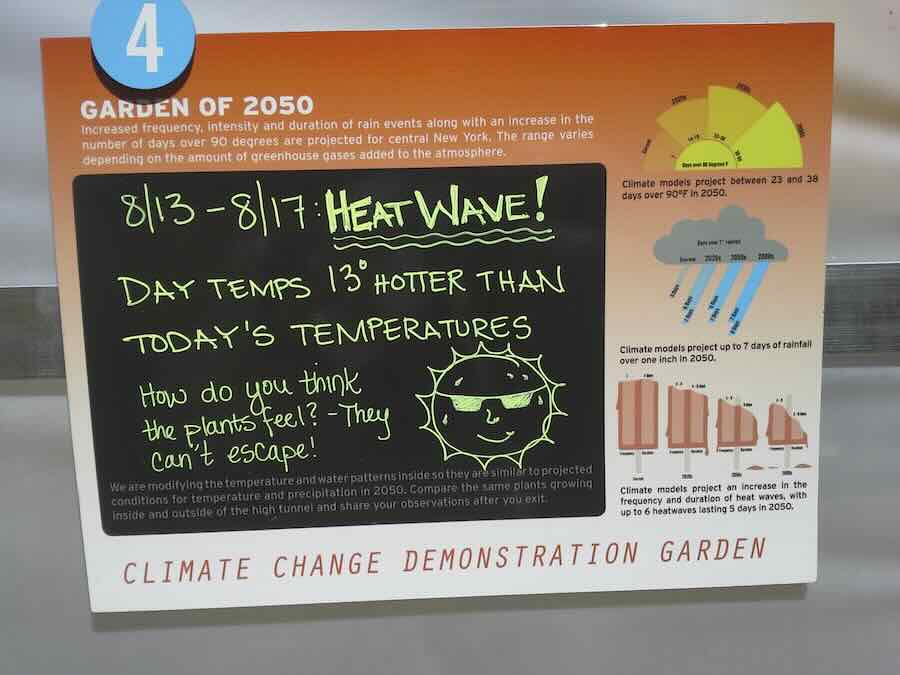

Sonja: Yes, thank you. It is a small garden and it’s placed within our vegetable garden, where we also do some demonstrations about sustainable gardening practices. And it’s… I’m not sure of the square footage, but it contains a high tunnel, which is basically a simple greenhouse with like a plastic cover over a steel frame. And there are six raised beds inside of it, and then just outside of it is another set of raised beds, six of them.

And the idea is that outside is today’s climate, it’s what’s happening now, what you would see in your garden. And inside this greenhouse, we are manipulating the temperatures in there to approximate what may happen in the year 2050, according to different climate models. And what we’re trying to give visitors a sense of is what’s going to happen with the plants, and using the plants as the lens through which we look at how climate is going to affect these plants.

Margaret: Right. And I’ve read, I think in an article in Sierra Club magazine or newsletter recently, you were interviewed. And apparently you gave a tour to the person and you made it very clear. It was like, you stepped inside the greenhouse and it was uncomfortable. And then you stepped outside the greenhouse and it was more comfortable,. But you pointed out that the plants can’t step outside the greenhouse, can they?

Sonja: That’s right. So even though we’re using plants as the lens, I think that the temperature difference between outside and inside, when visitors walk through it, whether they’re on a tour with me or our other docents or garden staff, is it’s warmer in there. And some days it’s just, ambiently warmer because the greenhouse captures sunlight and holds it better than it does outside.

But when we are trying to approximate heat waves, which is what’s predicted for this area or more frequent and longer heat waves, we drop the sides of the tunnel down, or the sides of the greenhouse down, and it gets really noticeably warmer in there. And so it’s like you walk in and it just kind of hits you in the face, this heat.

And I try to keep people in there. I try to stand like if I’m leading the tour, I try to stand there for a little bit. So they have to experience it a little bit, and we talk about it and I make that point that, O.K., we can walk out now, but the plants are still here, and our children will still be here. So how are we going to address this?

Heat can promote certain pests and diseases and make them more successful. It interferes with water. It uses up the water faster. It has a lot of cascading impact. It’s not just heat.

Sonja: It’s heat and it’s frequency of water events. I know we’re coming, we’re still on a… I’d like to say we’re coming out of a drought, but we’re still in this drought this year. And I know at the gardens, it’s very hard on the plants. And what we’re trying to show in the garden and think about, we’re actually taking our cues from our native landscape, and looking at what plants that are perhaps going to be lost because the temperatures are going to get too high, or the way that the precipitation patterns change they’re not going to be able to survive.

But we’re also looking at what’s coming in both from always… At least I’m an optimist, so what are the opportunities here? And our seasons can be extended, and we might be able to grow things longer. But there’s also the flip side of that, which the way that we talk about the plants in the garden is that we have some winners and we have some losers. And one of the winners that we tried out were we actually planted weeds in the garden and…

Margaret: [Laughter.] Oh, you contrarian, you.

Sonja: Let me tell you. They did really well inside this warmer, inside the greenhouse, where it was warmer and approximating this warmer climate. So they grew faster. They put on more seeds and in this very confined space, we had to harvest them rather quickly. But in an agricultural setting, we can’t do that. Or in our gardens, it’s going to be harder to keep up with those weeds.

Margaret: So yeah, a scientist at the national botanic garden in D.C. told me that poison ivy likes the changing climate, and is going to advance faster. So people will be really happy to hear that, too [laughter]. So I’m trying to laugh, O.K.?

So what do we do? Do we change our planting times, or do we water differently? Or what is it that are these sort of top takeaways that you are already knowing for sure are action items, that we gardeners all need to implement sooner than later?

Sonja: Absolutely. One of our collaborators on this project is David Wolfe and he’s a professor of horticulture and he’s written a lot about how we can adapt our gardens to climate change. And he uses the phrase, “add depth from the bench” in your garden plantings. And I love that phrase. And to me, it basically means mix it up, add in more plants and add more biodiversity.

So the more biodiverse that our gardens can be, the greater our gardens will be able to adapt to these changes, and we’ll be able to see what works well, maybe what doesn’t work so well. If we’re having a particularly wet season, there may be something that doesn’t work well, but something else will work well, because of the likelihood of more droughts. There may be some plants that do well in that regard.

And it’s not just good for us and beneficial to us, but that increasing biodiversity also helps our ecosystem, especially the pollinators.

And so we looked at two plants, two groups of plants in the climate change garden, and both are food plants: food plants for humans, and then food plants for pollinators. And one of the problems that we’re anticipating is what we call phenological mismatch. That is, that the plants are going to be blooming at times, most likely earlier in the season than when the pollinators are around that need them and that the plants need to be pollinated by.

And so by increasing our native plant biodiversity, that can help those pollinators find something. It can also help in our garden and see what’s working and really help the ecosystem as well as, you know what we’re looking at out of our windows and enjoying from our patios.

And I just wonder with the vegetables, especially, I don’t know, young plants can’t hit into, I mean, they’re not going to do so well if they’re young and tender and then suddenly a drought is starting in June and they’ve only been in the ground a couple weeks. You know what I mean?

Sonja: I do.

Margaret: Yeah. The impacts.

Sonja: It’s hard. I’ll put a shout out to the botanic garden community around the U.S. So wherever your listeners may be from, you can go to your local botanic garden, because they’ve probably been dealing with this for a long time and have been trying to figure it out and how to care for their collections, and have been experimenting. So at Cornell Botanic Gardens, that’s what we’ve been doing with vegetable plants, but with also herbs and annuals, perennials, shrubs, trees is… You know, I started there 20 years ago and the director of horticulture then was bringing up plants that were not hardy for our zone and just trying them out.

And some of them, they have survived, and they’re in the landscape now. So in some ways, again, if you look at it from a positive perspective, you can start to diversify your landscape, maybe with things that we couldn’t grow 20 years ago. And we may have to, because we’re going to lose some of the things that aren’t going to be able to tolerate the changes in temperature and the changes in precipitation.

Margaret: So we want to provide that depth in the bench that you spoke about, that you cited Dr. Wolfe’s, one of his tenets of the future and so forth because we want to think about supporting pollinators, even if there’s that potential for mismatch phenologically and so forth of them being there at the wrong time, we want to have a good palette of things over a sustained period.

What are some of the other things: Should we change our planting and harvesting dates? Should we do water differently? Are you changing anything about that as a result?

Sonja: Well, we’re paying attention to our frost date. So it has always been Memorial Day weekend was always the benchmark. We wouldn’t put out anything that was going to be tender until that date. We have noticed in the last couple years we can be a little more flexible with that, but also knowing that we’ve got to have some kind of protective, what is it?

Margaret: Like Reemay or a row cover or some kind of-

Sonja: Thank you [laughter].

Margaret: … Oh no, no, look, I can never remember my name most days. So don’t worry about that [laughter].

Sonja: So yeah, something like that. If the frost does come as early as expected, then we can protect it. But in general, we’ve been able to get some of the things earlier in the ground and that’s great because then they get going a whole lot sooner in our garden.

Margaret: So you may take advantage of some of this, like the last frost is coming earlier and you may nudge the planting back a little bit, which would then mean on the other end, not bumping into the heat as young in their young lives. And so you might do that, but you’ve got to have a backup plan for protecting them, so that’s good.

And it seems like water is just so difficult. Keeping up with watering is so difficult. And it seems like targeted watering systems–everybody for years has been saying, oh, we should be doing drip or we don’t be spraying overhead, blah, blah, blah. But it seems like that’s even more relevant advice now. Are there any recommended insights about watering?

Sonja: I think what you just mentioned thinking about the localized watering, drip irrigation, is really good and using it where you can. And some of the practices of watering deep and long instead of just showering over the plants for a couple of seconds, but really getting the water at the soil, where it’s needed and for longer periods of time, trying to anticipate looking out at the weather and how much water may be needed.

We have tried that at different places in the garden and have been successful. And in other times we’ve just had to, we water all the time everywhere because that it’s just what’s needed and that there’s never enough.

One of the other things that we’ve done is looking at our native landscapes and taking our cue from them about plants that are doing well in these harsher more drought conditions, hotter temperatures, and what can we take from what’s happening in those landscapes and bring either the plants into our garden ,or having a nearby water source for them. And that’s kind of how we do that. And just trying to not use as much water even though our region is not predicted to have as severe drought as other parts of the U.S., we still are very aware of that possibility, and are trying to be conservative in what we use and where we use it.

Margaret: Yeah. I think that’s critical planet-wide to be aware of that, yeah. And so what about, I think in one of the articles I read about the project there in the demonstration garden, there was the recommendation about shrinking your garden’s carbon footprint. So what about that? Are you looking at till versus no-till and the impact or any other things like that about cultural methods?

Sonja: We do. There’s a handful of easy things to think about with the decreasing your carbon footprint. One is trying to use less carbon, and a lot of that carbon can come in the form of fertilizers, especially synthetic fertilizers. And if you can reduce your reliance on synthetic fertilizers and use more organic like manure and compost, the better, the less carbon you’re going to be using.

And the added benefit of that is that if you’re putting manure and compost into your soil, you’re improving the soil health. Which gets back to the question we were just talking about with water is that the healthier the soil, the greater the capacity is to hold that water. Or if we’re in a heavy rainfall situation, it helps the water drain quicker, too. So it’s got these added benefits. It takes a little bit more input on our part. We can’t just apply a liquid fertilizer. We’ve got to work that organic matter into the soil or put it on as a top layer, but it’s in the long run, it’s so much more beneficial.

Margaret: Yeah, I think I’ve been forever old hippie type of mentality [laughter] and I’ve been an organic gardener forever and I’m a compost person and I just topdress and so forth. And I have definitely moved away from cultivating my vegetable beds, and instead just cleaning up a little bit and making room with my fingers or a smaller implement or whatever for getting those next seeds or seedlings in each year, because turning this tilling does release unwanted elements into the environment.

So the no-till even on our small garden levels is, I think, something else that we can do.

Sonja: That’s true. And if we’re mowing, leave those clippings, put your lawn mower on compost cycle and just leave them. I love this phrase, “leave it a lawn.” [Laughter.] I didn’t make it up, but I love it because I continue to leave it a lawn.

Margaret: Leave it a lawn.

Sonja: And the other thing you can do, we’re talking about mowing is just mow higher because then those grass roots go deeper and they go farther out and they’ll be better able to withstand drought conditions because their roots are deeper and they go out farther, that’s a really good practice.

And then the other thing, and we have this at the botanic gardens is a native lawn where we’re using native and low-growing grasses instead of the traditional grasses that are often placed in our lawns. And what’s nice about those is you don’t have to mow them at all. So you can just get away from having a lawn mower altogether.

And a lot of what we have in our native lawn is an oat grass, Danthonia, two different species of Danthonia and that seems to work really well. And then we’re able to interplant it with some meadow and woodland herbs for some color. And if you walk on it, then they’re very fragrant. So there’s different ways that you can do that.

Margaret: So besides not utilizing the resources required in mowing, it’s also providing pollinator support and other insect support and food and habitat. And who knows what. These kind of groundcovers as opposed to a mown turfgrass situation.

Sonja: Absolutely.

Margaret: Yeah. So that’s been a big part of what you’ve been doing there, too. That’s been an important part of the botanic gardens’ work, I think, also.

Sonja: And I’ll just add that there’s one other technique that we used, especially over COVID when we didn’t have very many visitors and we weren’t on campus as much to care for the garden as much: We planted those six—well there are 12 garden beds in total—we planted several of them in cover crops. So things like clover so that we could just keep the soil healthy and it didn’t dry out totally. But the benefit of that is it does that in between as an organic farmer, it’s a good in-between crop. And then if a lot of those cover crops, if you work them back into the soil, add that organic nitrogen and other nutrients instead of using a synthetic fertilizer.

Margaret: Yeah. We used to call it green manures. I don’t know if people use that term anymore, but green manure. So it’s like you’re growing your own green manure to turn in to-

Sonja: It is.

Margaret: If you don’t have a cow or chicken, right [laughter]? Which cover crops? Everyone always asks me about that. Did you try different ones or do you have favorites yourself, for instance, that for fall and we’re both in a colder zone, so we have winter to contend with. Did you do grasses or legumes or mixes or?

Sonja: It’s mostly legumes that we’ve been using.

Margaret: So which crops would you like, field peas or things like that?

Sonja: Yes, I think that’s the one in-

Margaret: Yeah. That’s the one that I’ve used that sometimes, and sometimes I’ve mixed it with oats, I think. And it’s been interesting to see compared to the old… It used to be that all you could get was winter rye, but now a lot of the seed companies have a lot more diversity of cover crops available in smaller amounts for home gardeners, too, which is great. Because it used to be, it was a farm thing. It wasn’t, you couldn’t get…

Sonja: But doesn’t have to be on that large scale. You can do it on a small scale, too.

Sonja: It is a true thing. I haven’t offered in a few years, but yes, it’s a class and there are other classes at Cornell that now offer some of the things that I covered in that class. And the idea behind it was that in addition to just gardening, there are many other ways that plants are good for us. So time and nature time spent with your hands in the soil, working around plants, being around plants, even if it’s not in an interactive way, just looking at them. There’s a lot of research now that shows that, that is beneficial to our wellbeing, helps reduce our stress.

It can help the way we learn, how much we retain. So we talk with students here at Cornell, a lot about it. And we have a partnership with the Cornell health program here to really help students realize just how good nature and being around plants can be. So if they’re stressed, they’ve got a test coming up, we tell them 20 minutes outside looking at the trees, not on your phone, not cramming for your test, can be more beneficial to you and help you do better on that test than cramming.

Margaret: And the “not on your phone” thing, you must as an educator in a university, you must just see… Because the students are digital natives, so to speak, they’ve been on the phone or the computer, their whole lives. It just seems like our heads are in there. And you’re absolutely right. I mean, even those 20 minutes for me, even just looking out the window helps compared to staring into the screen, right [laughter]?

Sonja: It’s true. And I will say that as somebody who has studied this and somebody who tries to practice it, it’s hard to do sometimes. I have to remind myself, get off, step away from the computer, go outside in this beautiful botanic garden in which you work and de-stress for just a little bit. And as soon as I do that, it’s really helpful.

Margaret: Yeah. Are you a home gardener, too? Or do you get enough of it having all these projects and responsibilities at work? Are you a houseplant person or a backyard gardener or anything?

Sonja: I am both. So I try to take home what I learn at the gardens from my colleagues and put it into place. And I was just noticing the other day, for years, I’ve been reading about creating these native habitats and bird-friendly and pollinator-friendly habitats. And you need water, you need a diversity of plants. Having some bird seed is good, but other plants that they can get seed from, having places where they feel protected.

And I was looking out my window the other day, and I thought I’ve done it. Because all of those things, bringing in native plants, having that water source, I don’t know that it would meet our aesthetic at the botanic garden level, but for my home landscape, it’s true. And then all those pollinators, whether they’re birds or they’re insects, they just add that more beauty to that landscape.

Margaret: Well-said, and boy, at Cornell, you have the Lab of Ornithology as inspiration and so many resources there, so I’m jealous. We’re just about out of time. And I just wanted to say thank you so much again. I know it’s sort of that busy back-to-school time and I really appreciate your taking the time and also just to know about, and I’ll give links about the work you’re doing [below], where people can see more about it. And it’s just so important and the tips that you’ve given us today, I much appreciate Sonja. So thank you so much for making time.

Sonja: Thank you so much for talking with us and yes, thank you for sharing the links because there’s work that my colleagues are doing that I think would benefit a lot of your readers, and just knowing about how they can do some of these things at home. And if they want some of the science behind all of this, where we’re getting our climate data and how we’re using that, those are very helpful. too.

Margaret: We’ll definitely give those in the transcript as you shared them with me. So thank you so much. Talk to you soon again. I hope.

more about cornell and its botanic gardens

prefer the podcast version of the show?

[ad_2]