[ad_1]

A Maryland judge ruled a community group provided “overwhelming evidence” that a portion of a Maryland apartment complex served as a cemetery for freed Black slaves.

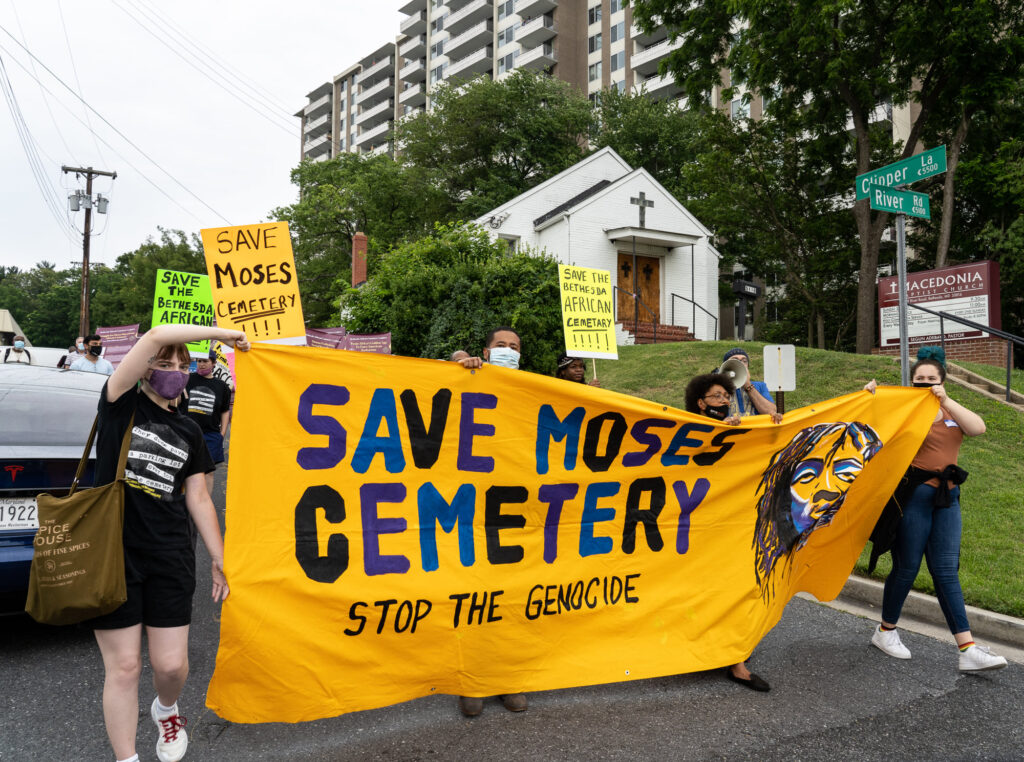

The Montgomery County Housing Opportunities Commission’s (MCHOC) $50 million sale of Westwood Towers in Bethesda to Charger Ventures drew intense opposition from the public, which led to the Bethesda African Cemetery Coalition filing a lawsuit.

According to NBC News, the group furnished historical accounts indicating Moses Cemetery was paved over during the 1960s when the apartments were built. The coalition accused the MCHOC of violating state law by failing to seek and receive court approval for the sale, which is required when a cemetery property is involved.

Judge Karla Smith of the Montgomery County Court denied a motion by the MCHOC seeking to dismiss the suit and granted the coalition a preliminary injunction stopping the sale.

“Regardless of whether Charger decides to keep the parking lot, build on the lot, or dig up the lot, bodies of African Americans remain there,” Smith wrote, adding that “the Court has an obligation to ensure that such resting place is respected.”

Moses Cemetery was active from 1911 to 1958 and is one of the last remaining landmarks of Bethesda’s historic Black community. Last month, community members testified in an emergency hearing. Those who testified included Harvey Matthews, one of the only surviving members of the Black community in Bethesda.

Matthews, who has been fighting for the cemetery for years, testified that when he was a boy, the cemetery had more than 200 grave markers, many of which were during the construction of Westwood Tower.

In her decision, Smith said it was paramount to hear from the descendants of those buried at the cemetery and who previously lived in the community.

“The Court cannot ignore that Plaintiffs, African Americans, are seeking to preserve the memory of their relatives and those with whom they share a cultural affiliation,” Smith wrote according to Yahoo. “Nor can the Court ignore that as early as the 1930s when construction began in the River Road community, the deceased have been forgotten, forsaken and their final resting places destroyed or, at a minimum, desecrated.”

The MCHOC told NBC in a statement Tuesday it will continue to pursue a legal path that will allow the sale.

[ad_2]