[ad_1]

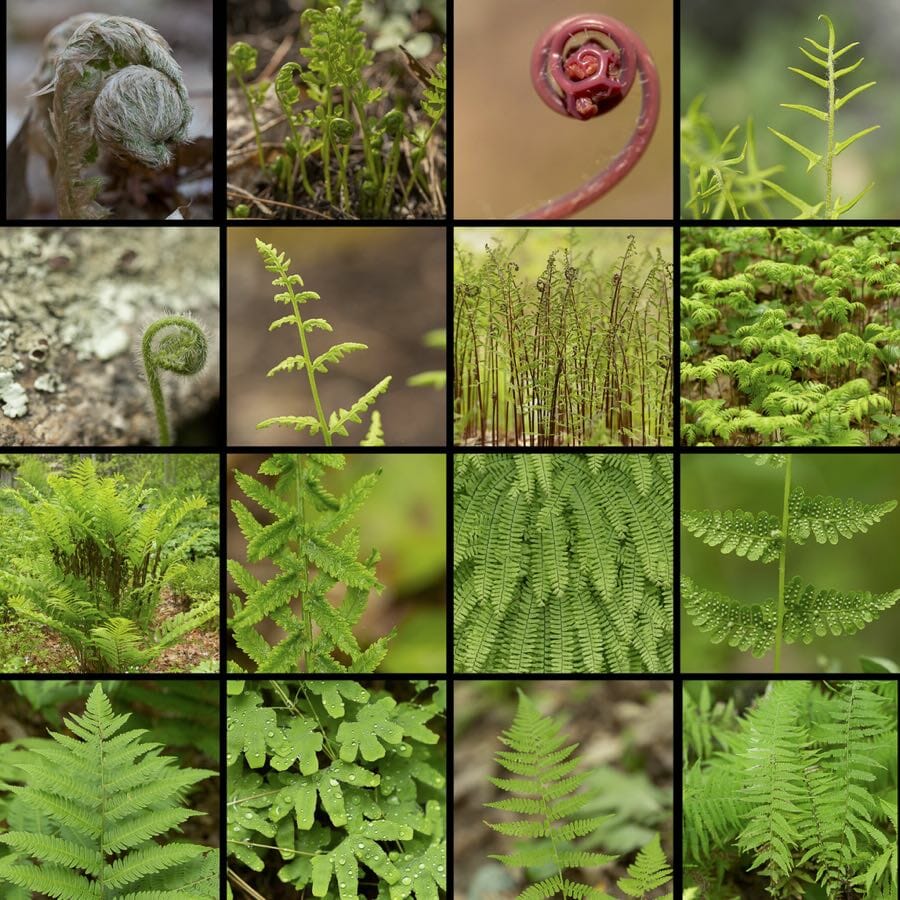

As delicate as they might look texturally from the moment of their first emergence in spring, though, the ones that always startle me by their incredible toughness are the ferns. That’s our topic today, ferns—and specifically native ones—with Uli Lorimer of Native Plant Trust, who will tell us some fern lore, and some fern care, and even how they reproduce so we can propagate more of them ourselves.

Uli Lorimer has made a career of working with native plants. He was longtime curator of the Native Flora Garden at Brooklyn Botanic Garden, and in 2019 became Director of Horticulture at Native Plant Trust, the former New England Wild Flower Society, and America’s oldest plant conservation organization, founded in 1900.

Read along as you listen to the Aug. 2, 2021 edition of my public-radio show and podcast using the player below. You can subscribe to all future editions on Apple Podcasts (iTunes) or Spotify or Stitcher (and browse my archive of podcasts here).

Margaret Roach: I always look forward to our conversations; I always learn a lot. And before we begin, I just want to remind people two things they may not know about Native Plant Trust in Massachusetts:

You have great courses, including a lot of online ones. I see there’s one coming up in shade gardening, and another on native plant palettes, and more. So we’ll give links for people to look at that, but wow, you do a lot of education, don’t you?

Uli Lorimer: We sure do. We also have an author talk coming up featuring Darrel Morrison, who I worked with at Brooklyn Botanic Garden, and I’m fortunate to call a friend, and there’s information on our website as well to see how you can join in on that particular event, where he’s going to talk about his new book called “Beauty of the Wild.”

Margaret: Which is sitting right here on the left side of my desk right next to me [laughter]. Yes, very topical, very timely. And the other thing I was going to say to people: In case they’re in new England or taking a drive or whatever, besides visiting Garden in the Woods and the Nasami Farm, your other facility, you sell plants, don’t you, at both places?

Uli: We sure do. Yeah. So we propagate a lot of natives, a lot of native species. We’ve got a great availability list of things. If you’re in the area, please drop in, visit us in the garden and take some plants home.

Margaret: Yeah. Adopt some babies, huh? [Laughter.]

Uli: Indeed.

Margaret: So ferns, ferns, ferns, you have lots of great stories. You always tell me great things. Like why is a Christmas fern called a Christmas fern, for instance?

Margaret: Right.

Uli: But I’ve always been enamored with ferns, as you said, so very elegantly in the beginning. When they first emerge out of the ground, they’re beautiful, they look nothing like what they are going to become once they’re fully expanded. They’re tough. They’re very ancient plants. And I think they have just a really wonderful calming presence and texture in the garden. And so I love talking about them. So I’m actually very thrilled that we have a chance to share some of those stories. [Above maiden hair fern emerging.]

Margaret: So why Christmas do you think, why is it called Christmas? What is it: Polystichum acrostichoides or some word like that?

Uli: Yeah, it’s a mouthful, but so Christmas fern is an evergreen Fern. It’s a clump-forming fern. It’s pretty common here in the region. And if you look at the individual frond, at the individual pinna—so that’s one like a little leaflet on the frond—you’ll see that it has a little boot shape at one end. And it looks like a Christmas stocking.

That’s a reason why it was called Christmas fern, in addition to the fact that it was collected for Christmas reads and other things at that time of year. So it’s a really wonderful sort of connection with the human uses of this nice plant. And also I think just a cute story that next time you’re out there, you can take a look for yourself and take a look at the little stocking.

Margaret: Very cute. You told me something else the other day that I didn’t know about ferns and their sort of history among protected plants in the United States.

And I think at the time, the fine was something like $5, which doesn’t sound a lot now, but in those days, I’m sure it was fairly hefty. Unfortunately, many botanists agree, that this plant never really recovered from the over-harvesting that it suffered from at that time. And it’s always been an uncommon plant and in some cases, a very rare plant now, because there’s habitat loss, invasive species, and all the other reasons and challenges that ferns face. But it’s a neat story because in the United States history, in terms of plant-protection laws, a fern was the reason for the very first one.

Margaret: Well, it’s interesting that they led the way in that, because I remember a story about them leading the way in general. Years ago, speaking to the late Dr. Elizabeth Farnsworth, who was with New England Wild Flower Society, when it was called that (now Native Plant Trust). And she was a fern lover and a fern expert. And I said, “Well, so they don’t flower. They don’t have pollen. They don’t have nectar. What’s their purpose? What’s their ecological service that they provide if they’re non-flowering plants?” And she said—and I’m not quoting, I’m paraphrasing—she said, well, think of all the creatures that can use them as habitat because they’re like groundcover so to speak, low vegetation.

And also she said, they’re early colonizers of disturbed spaces like ferns march in kind of and habit the ground. And I had this experience recently, I had to cut down two smallish, ornamental trees, things I planted, not any big native trees. So it kind of created this bare space in the shape of a bed, but there wasn’t much below them because it had been so shady. And within what seemed like minutes sensitive fern. And I think hay-scented is the other one that just kind of showed up [laughter].

Uli: Yeah, they’re really good at moving into space, those two particularly. The other thing I find amazing about them is that they’re ancient. I mean, we’re talking about hundreds of millions of years ago that ferns evolved, and despite the absolute explosion of flowering plants and the diversity of flowering plants, there still are 15,000 species of ferns and fern allies on the planet. So they’re still quite successful despite kind of a difficult way that they can reproduce themselves. So I’m just amazed of their sort of staying power in the face of plants that are much better at getting and moving around.

Margaret: So “difficult:” That brings up the subject that we promised you are going to kind of unlock a little bit for us about how do ferns reproduce, and what can we kind of learn from that understanding to propagate some ourselves, I guess.

And so the way in which those are arranged on the backside of the frond can help you identify them. So the spores have to be released and blown or washed into a favorable place where it can germinate. And it creates this little structure, it’s kind of like a heart-shaped leaf, called a prothallus. And on the surface of that, it then produces a male structure and a female structure. Again, you need water present to unite the two, and then once it’s been fertilized, it can actually grow what most people would think looks like ferns. [Above, Dryopteris marginallis prothalli.]

So the first kind of frond emerges out of that. And so it’s really a plant that needs to have just the right kind of conditions to be able to do it on its own. That said, growing them yourself really isn’t very difficult. We’ve got a really wonderful tip sheet on our website called “Growing Ferns from Spores” that was written by Bill Cullina when he was here at New England Wild Flower Society.

And really what you need is patience need to be able to collect the spores and it tells you how to do that. But the most important thing is sterile conditions. And you can take a small pot of soil, he recommends microwaving it, and then you sow the spores onto the surface, and then close the whole thing up into a Ziploc bag or creating a mini-greenhouse. And then you put it on a sunny window and you wait.

And within weeks, you’ll begin to see what looks like a little green fuzz on the surface. And those are those little prothalli that I talked about. And then within 10, 11 weeks after you’ve sown it, you should be able to see the beginnings of the new fronds emerging. And when they’re big enough to handle, you can take them out of the bag and divide them gently, and then grow them on as you would a normal plant. They don’t grow fast, so you definitely have to have patience, but it’s not as difficult as people might expect it to be.

Margaret: Another thing that I noticed in the garden is that certain species… I mentioned that some just sort of seemed to appear lustily [laughter], but sometimes I notice with painted fern, with Japanese painted fern—not a native fern, obviously—I see babies. I was going to say seedlings, but of course they don’t have seeds, they have spores, so they’re not seedlings.

But I see little babies, volunteers, in the cracks and crevices adjacent to the area where the adult plants are growing. So it’s funny that some of them do seem to sow themselves around successfully, even in a garden setting. And probably if I didn’t clean up as much in certain areas, I’d have more that made it.

Uli: Yeah. Well, I mean that, again speaks to the extreme microclimate in the crevice and crack in between the rocks it’s probably just sheltered and moist enough for the painted fern and its spores to undergo this very sensitive early period, and then be able to start growing new fronds. It definitely does happen, but it’s sort of a cryptic process because it’s a stage of life that many people don’t actually witness because it’s very tiny, and it kind of happens underneath and hidden from view, unless you’re really trying to go out and look for it.

Margaret: So let’s say it was getting to be fall, I guess probably is that when a lot of them sort of ripen these spores—later in the season?

Uli: Well, there’s a whole range. So the very first one to come ripe is Interrupted fern, Claytonia. And that’s ripe already, as soon as May. And then it extends all the way through until late November when climbing fern becomes ripe.

What you need to do is you have to check them periodically and kind of like you do a spore print, you clip a frond, you bring it indoors, you put it on a piece of paper and some are where it’s not drafty. And then you wait overnight and it dries out and then we’ll leave a spore print on the piece of paper that you can then tip into a little envelope and you’re good to go.

Margaret: O.K. So those are the ones that have… Is it called sori? What are the little dots on the back of the fronds called that have that?

Uli: Yeah, so the spore bank structures are called sori, right? Some of them have a little covering, sort of like a thin white covering on the top, that’s called an indusium. It’s going to kind of peel away. And then when they look brown, then it’s usually good, and sort of a darker brown. Some of them may start off more of a tan color, which means they’re not quite mature yet, but once they’ve turned a good dark brown color they should be ready to be harvested.

Margaret: O.K. So then I have a obsession with speaking of ferns that like to take over territory. I love ostrich fern, and that has a different way of making its spores, I think, with fertile fronds. Is that correct?

Uli: Yes. So this is a great distinction to make. So some ferns will combine the fertile frond with the frond itself, and then others will separate the two, so they’ll make sterile fronds. So that’s basically the solar panels for the plant, so they can capture light energy. And then they’ll make a separate fertile frond, which looks very different than the sterile frond, and that is entirely designed to create the spores and get them out into the environment.

Margaret: So with my ostrich fern, I wouldn’t find any of those little dots, those sori, on the back of the green foliage, but I might cut back one of these brown… And they’re very persistent; I leave them up in the winter and they’re beautiful. And I would bring that in and put it on the piece of paper, out of a draft?

Uli: Yes. Exactly.

Margaret: O.K.

Uli: The ostrich fern actually also makes really wonderful winter arrangements. If you like arrangements and those sorts of things with grasses, we oftentimes include ostrich fern because they’re so architectural. And they last a really, really long time.

Margaret: They’re fabulous. So it spreads, and maybe we can just quickly mention among some native ferns that you’re crazy about—and of course, you’re in the Northeast and some of these have a wider range that you may mention and some not so. But some others that spread a lot versus some are for some particular, some favorites of yours that are for particular types of conditions.

Ferns in general have silicates in the fronds, and the deer don’t want to eat it. And so they’ll eat everything else but the ferns. And so when you see this kind of landscapes, it looks kind of beautiful and park-like, it’s because the deer have eaten everything else, except the ferns. So it’s visually beautiful to see big mature trees and this understory of like unbroken hay-scented fern, but it’s not a good long-term picture, because there’s no younger trees that are going to come up and replace them, because they’ve all been eaten off.

Margaret: Right.

Uli: Sorry, it’s a depressing aside.

Margaret: No, no, no, but I get it. I mean the lack of diversity, and really all you’ve got is some of the older trees and then this fern and that’s it. Everything else has been chomped down on.

And they’re all about the same height and it’s just a wonderful combination. So that’s definitely a big favorite of mine.

I’ll give you one other one, which is a little bit on the unusual side, which is called Northern oak fern, Gymnocarpium dryopteris is its name [photo, bottom of page]. And it’s absolutely darling. It grows about 6 inches tall and looks like a little mini bracken fern. And it’s a really wonderful one to pair with a more delicate combinations, so bunchberries [Cornus canadensis] or a wintergreen [Gaultheria procumbens], smaller plants that would normally be overwhelmed with larger, stronger-growing ferns.

Margaret: I’ve never seen that. Gymnocarpium dryopteris, is that what you said?

If you live somewhere where if you’re at elevation or in the mountains, there are two good sort of mountain wood ferns, Dryopteris campyloptera and carthusiana are two that have fronds that are almost sort of twice-cut, so they have this really lacy, frilly appearance that I think are really fantastic.

And then for wetter areas, things like royal fern, Osmunda regalis [above], which can almost grow in standing water and over time forms this really beautiful sort of dark brown root mass out of which the fronds emerge. And it creates its own little hummock and then other things seed into the root mass, and you almost have your own little ecosystem there, all thanks to one fern’s presence. So those are just a couple of my favorites.

Margaret: So those are some good ones. And again, some I don’t know. So I know I’m going to go madly, look them up as soon as we’re finished [laughter]. And so just to say quickly, of course, some of them, or another way to propagate ferns is asexually we could propagate them by moving them around, either taking pieces of those rhizomes of summer, taking a whole clump and so on and so forth, and which I do a lot.

And I tend to do it at the moister times of year, either early-ish in spring or sometimes even early in the fall, and keep them watered. But I tend to do that and they do really well.

But you told me the other day about a fernery—that there’s something called a fernery. Tell us what a fernery is because it was such an old-fashioned idea. Tell us what a fernery is.

And there’s only one in the United States at this point, it’s at the Morris Arboretum in the University of Pennsylvania, it’s called the Dorrance H. Hamilton Fernery. And it’s a really cool space; if you’re ever in the Philadelphia area, definitely drop in and check it out because there’s just an amazing amount of diversity in texture of ferns, primarily tropical ferns.

And then if you’re ever traveling in Europe, one of the things that I’d love to do when I travel is to visit other gardens. And there are loads of wonderful ferneries in England and Scotland and France, and they’re well worth seeking out. [Above, the fernery at the Benmore Botanic Garden in Scotland.]

Margaret: O.K. I’ve never been to a fernery, so see now that’s on my bucket list. I’ve got to go to a fernery.

Uli: I wish more people did them here.

Margaret: Yeah. Well, Uli, it’s always fun to talk to you and I hope we’re going to visit again soon. And again, I’m going to give links to some of the classes, and about the plants that are for sale at the various Native Plant Trust facilities and so forth [links below], to encourage people to engage with this great and very historic organization in its own right. So thanks for making the time today.

Uli: Absolutely. As I said, it’s always such a pleasure to speak with you, and I really relish the opportunity.

Margaret: Aw, you’re sweet. Well, thank you again.

(Photos by Uli Lorimer.)

prefer the podcast version of the show?

[ad_2]