[ad_1]

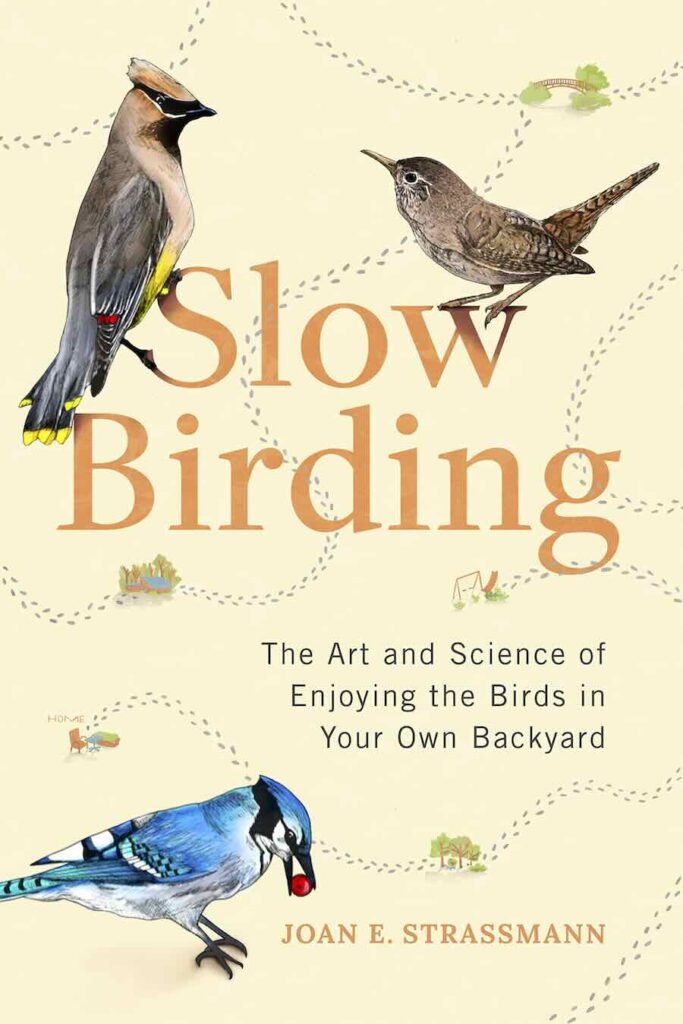

Dr. Strassmann is a specialist in animal behavior who’s a professor of biology at Washington University in St. Louis. She’s also now the author of “Slow Birding: The Art and Science of Enjoying the Birds in Your Own Backyard” (affiliate link).

Plus: Enter to win a copy of the new book by commenting in the box near the bottom of the page.

Read along as you listen to the Oct. 24, 2022 edition of my public-radio show and podcast using the player below. You can subscribe to all future editions on Apple Podcasts (iTunes) or Spotify or Stitcher (and browse my archive of podcasts here).

slow birding, with joan strassmann

Margaret Roach: When I started reading the book and all I could think was: finally an official title for the way I watch birds [laughter]. So thank you.

Joan Strassmann: Oh, it’s my pleasure.

Margaret: So tell us what slow birding is. Give us the sort elevator pitch on what’s slow birding.

Joan: I guess I’ve been a slow birder all my life. I’ve taught some very focused bird classes, where I’ve had students watch birds. And kind of the minute I heard about the slow food movement, I thought, “Oh, we should have slow birding, and it should be just the same.” Where we watch things, we appreciate them, and we don’t just run around in a frantic way with our lives, moving from one thing to the other. So I’ve wanted to write this book for about about 20 years and I finally did it [laughter].

Margaret: So it’s not that kind of almost drive-by birding where if you’re into birds you can see an alert on one of the chats or whatever, the message boards, whatever. You hear from a neighbor or someone else that, “Oh, this was seen in such and such park,” or whatever, and you go and you want to check it off your list. It’s not that type of “listing” motivation. It’s really watching. Right?

Joan: Yeah, it’s watching. And then the reason I wrote a whole book about it, not just something short, is that I wanted to tell the stories of the commonest birds, because the commonest birds are also the most-studied birds, and the ornithologists have figured out some pretty amazing stories about them. So I also wanted to tell the stories of both the scientists and the common birds.

Margaret: So it’s not just your experiences in “Slow Birding” with these 16 species you include in the book, but you’ve introduced us to the people who have studied them perhaps the most, and their insights and their experiences. And so it’s deep that way; I mean, it goes really deep. Plus you give us, after you do each sort of species’ chapter, you give us tips on how to get to know that bird better. Sort of little exercises to do, which is also good, because it’s a reminder that we can engage and study them ourselves, I think.

Joan: Yeah. I did that because sometimes, you know, can tell people, “O.K., sit there and watch a blue jay for an hour,” and if you don’t have any idea what you might be looking for, it still can be very poetic and rewarding. But I always like to have something to count, something to draw and something to count. And so yeah, I just thought I would suggest some fun little things that you might do in your chair with your little notebook watching the birds.

Margaret: And so you also give, in the sort of initial chapter of the book, you give some prescriptive overall steps. And I want to talk about some of those closer to the end about how we can enhance… because this is about birding at home or in a space that’s familiar to us. But I want to mention one now, which is that we should create a home bird list. And I wonder if you could just tell us why. So in other words, not like a giant life list ,if we’re running all over the place hoping to see rare birds, but a home bird list. Yes?

Joan: Nice to know what is right around you, what you can expect. Here I’m waiting for the first juncos to appear. The white-throated sparrows have already shown up. So another nice thing these days about doing a yard list, or a 5-mile circle, or a list for a certain neighborhood park, is just do it in eBird and then you can look back through all your lists in eBird. You can sum them up. You don’t really have to do any of the management stuff, because eBird does that for us.

So once you pick a place in eBird, you can look back at that place in as many ways as you want to. So if you’re interested in the turnover of the seasons, which I think we all are, seeing what birds you saw when, it’s just, I don’t know, it’s enriching to me.

And that’s why I said I was so happy to see it sort of named something, because I feel like I know them, and I have this winter list, I know who’s here in the winter. I kind of keep it that way as well. I know who to expect at the cusps of the season, as you’re saying.

So these are not rare birds that you’re profiling. These are the most familiar birds really. And so I wanted to just dig into some of them.

The blue jay, everybody knows who a blue jay is. And so maybe a couple of the things that you talked about with the blue jays, their relationships. I mean, they really helped shape the flora of parts of North America, didn’t they?

Joan: As far as we can tell, they were important in bringing the oak trees north. I mean if you look at how quickly oaks moved north as the glaciers receded only about 10,000 years ago, they certainly didn’t do it on their own, and blue jays are our best current possibility. Some people think that the passenger pigeons were very important in that also. And that is sadly not a theory that we can test.

Margaret: So blue jays grabbing the acorns and moving them a mile away or a half a mile away, and that continuing movement aiding the distribution of the acorns to plant more oaks.

Joan: Right. And so you can watch that. You can watch a blue jay with an acorn. You can see that they take the caps off before they move. You can stop under an oak tree and see if the acorns still left there are the lighter ones that have weevil holes that the blue jays won’t have been interested in. So the tie of the blue jays to the acorns makes them an especially good bird for a slow birder.

Margaret: With some of the tips about blue jays and about getting to know them better. They have so many different vocalizations it seems like. They’re talky [laughter]. And you suggest that we sort learn more about some of their sounds and maybe even record them and so forth.

Joan: Yeah. They can fool… There’s another app from Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and these are all free, by the way. It’s called Merlin, and it will listen to the birds. When you have it turned on, it’ll listen to the birds. And blue jays can fool Merlin when they make the red-tailed hawk sound.

Margaret: They fool Margaret, too [laughter].

Joan: Yeah.

And you profile the robin as well. You talk about the robin, and I mean, that’s a bird that in so many parts of the country, we all know. We can sort of close our eyes and think, even people who aren’t birders, could close their eyes and think, “Oh, it runs a few steps and then it sort of cocks its head to one side as if maybe it saw something or heard something and then it goes for it.” It starts pecking out the soil and that worm is unearthed.

And so that about? That was a fascinating tale because is it that they’re hearing? Or is it that they’re seeing? What’s going on?

Joan: So it turns out it is that they’re hearing, and this is work by Bob Montgomerie and Pat Weatherhead [two Canadian scientists] who I guess they had read a paper that said it was about vibrations, and they were wondering if that were true or not. So they devised set of very nice little experiments to see what exactly it was that brought the robins so efficiently onto the worms.

Margaret: Right. And so we think, we infer, “Oh, Robins; they eat worms,” but is that really their primary diet?

Joan: They’re only eating worms when they’re feeding babies in large part. Robins are among the birds that eat the most fruit. I think they’re only surpassed by cedar waxwings.

Margaret: Yes. So it’s funny. So I don’t know what the word is, but they kind of pre-digest and then regurgitate the worms for the babies. Is that what the worms are like, baby food?

Joan: Yeah. Usually when birds are eating insects or arthropods or worms and all those sorts of things, it’s for the babies. And they don’t really digest them. They just kind of smoosh them up into their crop so they can carry a bunch of them to their starving babies.

Margaret: Right. And the other thing that I found was interesting is you sort of challenge us, you say, “Try to learn to tell the males apart from the females.” With robins, it’s not quite so obvious as with some birds, as with a pair of warblers or something. It’s a little trickier. And how do you suggest we learn to do that?

Joan: So, yeah, this is something I really hadn’t… I just thought you couldn’t tell robin’s apart. But if you look at them carefully, particularly in the breeding season, you’ll see that the male has a much blacker head than the female, and a much redder or russet-colored belly. He has much stronger colors than she does. And they’re often in pairs. They nest together, and both parents take care of the babies. So they provide you with a way of comparing, because you can often see both partners together.

So you just mentioned cedar waxwings in speaking of birds who like some fruit [laughter]. How in the world do they figure out exactly? Just before everything’s ripe, they swoop in. And I think in the book you say, “Cedar waxwings arrive unpredictably from on high.” It’s like they surprise me a lot in the garden. So tell us a little bit about cedar waxwings.

Joan: So cedar waxwings are true fruit specialists. They love fruit. They eat fruit. Even the babies get only about three days of mostly insects. I mean, they continue, but even the little ones can get fruit from very early, so that cowbirds often lay their eggs in cedar waxwing nests, but then the cowbird chicks die, because they just can’t make it on that very fruit-heavy diet.

Margaret: Oh. You call them “an improbable bird.” I mean, they really are just, they’re so beautiful. The markings on them are so beautiful, and they have that little whistle kind of a sound.

Joan: Right. And a lot of people, as they get older they can no longer hear that sound, which is sad.

Margaret: Oh, it’s too high-pitched, is that it?

Joan: Yeah, it’s too high. It’s one of the first birds that people with hearing loss, or even just slight hearing loss, lose. You know how the teenagers have these whistles that they can do on their phones that their teachers can’t hear?

Margaret: Oh my goodness [laughter]. Inspired by a cedar waxwing. That’s pretty funny. Their name cedar waxwing. I mean, I have a big old Eastern red cedar or Juniperus virginiana, in my front yard, and they love that tree. I think that’s where their common name picks up from, yeah?

Joan: Right, yeah.

Margaret: And they love shad, Amelanchier.

Joan: Right. They do, yeah.

Margaret: But how do they get… I mean really, they’ll just home in on shrubs or trees with fruit. It’s like they must have radar [laughter]. How do they know?

Joan: They’re social in the feeding stage. They’re just exploring all the time, and when they find a fruit tree, they don’t have to hide that information because there’s fruit for everyone. It won’t last that long, so they tell each other where the fruit trees are. I don’t know if your city has one of those apps where you can find out where the fruit trees are in the city that you can go pick the fruit. It’s kind of like that.

Margaret: Oh. Frugivorous or fruit-eating birds or whatever. I love Aralia, spikenards, so I have a number of different kinds, mostly native ones in the garden. And at Aralia fruit time, not just the waxwings, but also a bunch of different thrushes and so forth will come through and go crazy. And the one strategic error I made is I put a big stand of one of those plants near my patio [laughter]. It’s kind of messy because the birds, it’s like they eat it and it comes out the other side pretty quick. I mean, I don’t know if they even digest it, exactly what happens, but it’s processed pretty fast, isn’t it, the fruit?

Joan: Yes. There’s actually been studies of that, of how long fruit takes to go to through the gut versus things like insects. It goes through very fast. Yes, it has to, because it’s not terribly… It’s high in carbohydrates, obviously, but the birds do need protein and other things, so they just shoot that right through them.

Joan: I saw one this morning.

Margaret: Yeah. And so like the robins, when I see them, it’s often on the ground, but they’re looking for ants. Is that right? How in the world can it live on ants? So how does that work with the diet of the flicker?

Joan: Isn’t that amazing, that’s such a big bird could live on tiny little ants that you might see them picking out between the cracks in the pavement. I think that part of what that tells us is how little we see ants, because ants are among the most abundant of all organisms, and there’s plenty of ant biomass to support anybody.

Now they’re often underground. And when they’re underground, they’re not accessible to flickers. But flickers know where they come up, and the ants forage on the surface of the ground. So yeah, it’s just one of those little windows into the deep relationships that are right in front of us, but we don’t see unless we’re looking for them,

Margaret: Also, they’re cavity nesters. Well, they’re woodpeckers. I guess they’re our second largest woodpecker, I think. But so they’re cavity nesters, and they create the cavities that they live in. How do they tell a good tree? I think you say in the book that aspens are a favored tree, for instance. How do they-

Joan: Yes. Yeah. So they are a primary cavity nester. Karen Wiebe has studied these the most in British Columbia. And she says aspens are preferred. Aspens aren’t particularly long-lived trees, and they rot from the inside out, which I guess maybe that’s not that uncommon. But, yeah, they find an aspen that’s kind of at the exact right stage of rotting and chisel in their nests.

Margaret: So a half-dead tree, that as you say, it has a hollow core, you’re going to start excavating and you’re going to then get a bigger cavity pretty quickly because of that hollow core that you’re adjacent to. Right?

Joan: Right.

Margaret: I see.

Joan: Even if it’s not hollow, it could be rotting enough that the wood is soft.

Margaret: I see. And then you also say that they’re faithful birds.

Joan: I do. They are. And that may sound sort of obvious because birds look so happily paired up with each other. But in fact, most songbirds are not particularly faithful. Robins, almost every nest has chicks that are not fathered by the male that’s taking care of them. But flickers are faithful.

Margaret: So interesting. And that to me, again, I’ve watched them, they’re common where I am. I’m in a rural area, and a lot of good hunting grounds for them, so to speak, and a lot of trees; I’m surrounded by forests, so lots of places for them to nest. And their voices and their appearance, I mean, it’s just so common. And I knew about the ants, but I didn’t know about that they pair up like that. I didn’t know that.

Joan: Yeah, lots of birds pair up, but then both the males and the females go hunting around for other mating opportunities. Makes for great stories.

Joan: Yes. I mean, they were one of the birds that DDT nearly wiped out. And Bob Rosenfield’s story of how he began to study them. It’s just fantastic to be told to study a bird in a place you didn’t think it existed. It’s just, yeah, it’s really…

Margaret: And where did he do the work?

Joan: So he was a grad student in Wisconsin and was planning to move to a school in Virginia, but his advisor, I think it was University of Wisconsin at Steven’s Point, if I remember correctly.

Margaret: Yeah. That sounds right from the book, yes.

Joan: And he felt as an undergrad, he had taken all the classes, done everything he should have, and he was ready to move on to study the basic biology of Cooper’s hawks, what they needed to thrive. And at that time he thought, “Oh, they’re probably in the deepest forests and I’ll never find them.” So he did something that we’ve actually done, which is in those little throwaway newspapers that used to land in all of our yards from local groups, he put ads in, asking for Cooper’s hawk sightings. And to his surprise, he got lots of answers. But they weren’t in the deepest, most pristine forests. They were in the suburbs and there were plenty of them.

Margaret: Yeah, they love a good bird feeder [laughter].

Joan: They do.

Margaret: That’s a great target. And so in the last minute or two, I just wanted to talk about, at the start of the book, you give us sort of some tips, some things to think about to enhance the experience, especially in the home birding, like obviously put up a bird feeder. And I mentioned the other one, to create a home bird list. But let’s just maybe just outline a couple of the other of those tips to enhance our home environment for birding.

Joan: Well, most important, water. Birds love water.

Margaret: Yes.

Joan: It’s super-important to them. I have a little city lot. It’s 50 feet wide. It’s very small. We still put a pond in the backyard. In the winter, one of the first things I do in the morning is boil a tea kettle of water and pour it on the little shallow areas so the birds have some water. So water’s good. Native vegetation is good. Any of the flowers that have lots of seeds, the native flowers. We have lots of Rudbeckia, black-eyed Susans, and asters and stuff like that. And it’s just so rewarding to see the goldfinches hanging upside-down as they pull out the seeds.

Margaret: Yes.

Joan: So even in a small city lot, you can put some native plants and some water.

Margaret: Well, and I think the water can’t be overestimated as how powerful it is. And as you say, 365 days a year, not just in the fair weather.

Joan: Right.

Margaret: I could just talk to you forever about slow birding. And I appreciate your making the time today. And I’m just having fun reading “Slow Birding.” It’s a deep dive, but then again, there’s these tips that are so just what we can do, they’re simpler, too. There’s lots of science and lots of inspiration. And so thank you so much.

(All illustrations from the book, “Slow Birding,” used with permission.)

enter to win a copy of ‘slow birding’

I’LL BUY A COPY of “Slow Birding: The Art and Science of Enjoying the Birds in Your Own Backyard” by Joan Strassmann for one lucky reader. All you have to do to enter is answer this question in the comments box below: Are you a slow birder, and what bird do you feel you know best?

No answer, or feeling shy? Just say something like “count me in” and I will, but a reply is even better. I’ll select a random winner after entries close Tuesday November 1 at midnight. Good luck to all.

(Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.)

prefer the podcast version of the show?

[ad_2]