A Tale of Two Experts – A List Apart

[ad_1]

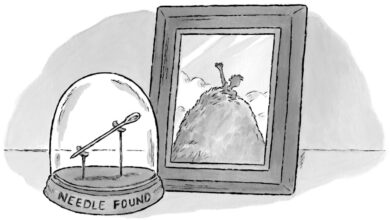

Everyone wants to be an expert. But what does that even mean? Over the years I’ve seen two types of people who are referred to as “experts.” Expert 1 is someone who knows every tool in the language and makes sure to use every bit of it, whether it helps or not. Expert 2 also knows every piece of syntax, but they’re pickier about what they employ to solve problems, considering a number of factors, both code-related and not.

Article Continues Below

Can you take a guess at which expert we want working on our team? If you said Expert 2, you’d be right. They’re a developer focused on delivering readable code—lines of JavaScript others can understand and maintain. Someone who can make the complex simple. But “readable” is rarely definitive—in fact, it’s largely based on the eyes of the beholder. So where does that leave us? What should experts aim for when writing readable code? Are there clear right and wrong choices? The answer is, it depends.

In order to improve developer experience, TC39 has been adding lots of new features to ECMAScript in recent years, including many proven patterns borrowed from other languages. One such addition, added in ES2019, is Array.prototype.flat() It takes an argument of depth or Infinity, and flattens an array. If no argument is given, the depth defaults to 1.

Prior to this addition, we needed the following syntax to flatten an array to a single level.

let arr = [1, 2, [3, 4]];

[].concat.apply([], arr);

// [1, 2, 3, 4]When we added flat(), that same functionality could be expressed using a single, descriptive function.

arr.flat();

// [1, 2, 3, 4]Is the second line of code more readable? The answer is emphatically yes. In fact, both experts would agree.

Not every developer is going to be aware that flat() exists. But they don’t need to because flat() is a descriptive verb that conveys the meaning of what is happening. It’s a lot more intuitive than concat.apply().

This is the rare case where there is a definitive answer to the question of whether new syntax is better than old. Both experts, each of whom is familiar with the two syntax options, will choose the second. They’ll choose the shorter, clearer, more easily maintained line of code.

But choices and trade-offs aren’t always so decisive.

The wonder of JavaScript is that it’s incredibly versatile. There is a reason it’s all over the web. Whether you think that’s a good or bad thing is another story.

But with that versatility comes the paradox of choice. You can write the same code in many different ways. How do you determine which way is “right”? You can’t even begin to make a decision unless you understand the available options and their limitations.

Let’s use functional programming with map() as the example. I’ll walk through various iterations that all yield the same result.

This is the tersest version of our map() examples. It uses the fewest characters, all fit into one line. This is our baseline.

const arr = [1, 2, 3];

let multipliedByTwo = arr.map(el => el * 2);

// multipliedByTwo is [2, 4, 6]This next example adds only two characters: parentheses. Is anything lost? How about gained? Does it make a difference that a function with more than one parameter will always need to use the parentheses? I’d argue that it does. There is little to no detriment in adding them here, and it improves consistency when you inevitably write a function with multiple parameters. In fact, when I wrote this, Prettier enforced that constraint; it didn’t want me to create an arrow function without the parentheses.

let multipliedByTwo = arr.map((el) => el * 2);Let’s take it a step further. We’ve added curly braces and a return. Now this is starting to look more like a traditional function definition. Right now, it may seem like overkill to have a keyword as long as the function logic. Yet, if the function is more than one line, this extra syntax is again required. Do we presume that we will not have any other functions that go beyond a single line? That seems dubious.

let multipliedByTwo = arr.map((el) => {

return el * 2;

});Next we’ve removed the arrow function altogether. We’re using the same syntax as before, but we’ve swapped out for the function keyword. This is interesting because there is no scenario in which this syntax won’t work; no number of parameters or lines will cause problems, so consistency is on our side. It’s more verbose than our initial definition, but is that a bad thing? How does this hit a new coder, or someone who is well versed in something other than JavaScript? Is someone who knows JavaScript well going to be frustrated by this syntax in comparison?

let multipliedByTwo = arr.map(function(el) {

return el * 2;

});Finally we get to the last option: passing just the function. And timesTwo can be written using any syntax we like. Again, there is no scenario in which passing the function name causes a problem. But step back for a moment and think about whether or not this could be confusing. If you’re new to this codebase, is it clear that timesTwo is a function and not an object? Sure, map() is there to give you a hint, but it’s not unreasonable to miss that detail. How about the location of where timesTwo is declared and initialized? Is it easy to find? Is it clear what it’s doing and how it’s affecting this result? All of these are important considerations.

const timesTwo = (el) => el * 2;

let multipliedByTwo = arr.map(timesTwo);As you can see, there is no obvious answer here. But making the right choice for your codebase means understanding all the options and their limitations. And knowing that consistency requires parentheses and curly braces and return keywords.

There are a number of questions you have to ask yourself when writing code. Questions of performance are typically the most common. But when you’re looking at code that is functionally identical, your determination should be based on humans—how humans consume code.

Maybe newer isn’t always better#section4

So far we’ve found a clear-cut example of where both experts would reach for the newest syntax, even if it’s not universally known. We’ve also looked at an example that poses a lot of questions but not as many answers.

Now it’s time to dive into code that I’ve written before…and removed. This is code that made me the first expert, using a little-known piece of syntax to solve a problem to the detriment of my colleagues and the maintainability of our codebase.

Destructuring assignment lets you unpack values from objects (or arrays). It typically looks something like this.

const {node} = exampleObject;It initializes a variable and assigns it a value all in one line. But it doesn’t have to.

let node

;({node} = exampleObject)The last line of code assigns a variable to a value using destructuring, but the variable declaration takes place one line before it. It’s not an uncommon thing to want to do, but many people don’t realize you can do it.

But look at that code closely. It forces an awkward semicolon for code that doesn’t use semicolons to terminate lines. It wraps the command in parentheses and adds the curly braces; it’s entirely unclear what this is doing. It’s not easy to read, and, as an expert, it shouldn’t be in code that I write.

let node

node = exampleObject.nodeThis code solves the problem. It works, it’s clear what it does, and my colleagues will understand it without having to look it up. With the destructuring syntax, just because I can doesn’t mean I should.

Code isn’t everything#section5

As we’ve seen, the Expert 2 solution is rarely obvious based on code alone; yet there are still clear distinctions between which code each expert would write. That’s because code is for machines to read and humans to interpret. So there are non-code factors to consider!

The syntax choices you make for a team of JavaScript developers is different than those you should make for a team of polyglots who aren’t steeped in the minutiae.

Let’s take spread vs. concat() as an example.

Spread was added to ECMAScript a few years ago, and it’s enjoyed wide adoption. It’s sort of a utility syntax in that it can do a lot of different things. One of them is concatenating a number of arrays.

const arr1 = [1, 2, 3];

const arr2 = [9, 11, 13];

const nums = [...arr1, ...arr2];As powerful as spread is, it isn’t a very intuitive symbol. So unless you already know what it does, it’s not super helpful. While both experts may safely assume a team of JavaScript specialists are familiar with this syntax, Expert 2 will probably question whether that’s true of a team of polyglot programmers. Instead, Expert 2 may select the concat() method instead, as it’s a descriptive verb that you can probably understand from the context of the code.

This code snippet gives us the same nums result as the spread example above.

const arr1 = [1, 2, 3];

const arr2 = [9, 11, 13];

const nums = arr1.concat(arr2);And that’s but one example of how human factors influence code choices. A codebase that’s touched by a lot of different teams, for example, may have to hold more stringent standards that don’t necessarily keep up with the latest and greatest syntax. Then you move beyond the main source code and consider other factors in your tooling chain that make life easier, or harder, for the humans who work on that code. There is code that can be structured in a way that’s hostile to testing. There is code that backs you into a corner for future scaling or feature addition. There is code that’s less performant, doesn’t handle different browsers, or isn’t accessible. All of these factor into the recommendations Expert 2 makes.

Expert 2 also considers the impact of naming. But let’s be honest, even they can’t get that right most of the time.

Experts don’t prove themselves by using every piece of the spec; they prove themselves by knowing the spec well enough to deploy syntax judiciously and make well-reasoned decisions. This is how experts become multipliers—how they make new experts.

So what does this mean for those of us who consider ourselves experts or aspiring experts? It means that writing code involves asking yourself a lot of questions. It means considering your developer audience in a real way. The best code you can write is code that accomplishes something complex, but is inherently understood by those who examine your codebase.

And no, it’s not easy. And there often isn’t a clear-cut answer. But it’s something you should consider with every function you write.

[ad_2]