seed catalogs to love, with jennifer jewell

[ad_1]

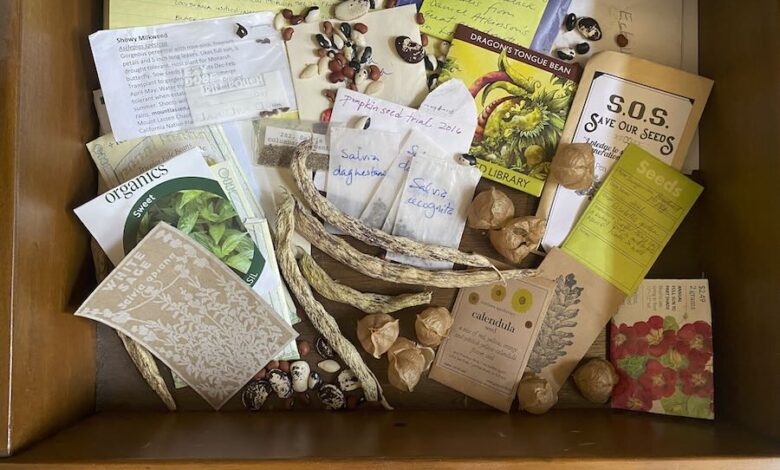

Jennifer’s latest book is “What We Sow: On the Personal, Ecological, and Cultural Significance of Seeds” (affiliate link) and she is the creator of the popular “Cultivating Place” podcast. We talked about how to choose a seed catalog, why regionality matters, and more. (That’s a peek in Jennifer’s seed drawer at home, above.)

Plus: Enter to win a copy of “What We Sow” by commenting in the box near the bottom of the page.

Read along as you listen to the Dec. 18, 2023 edition of my public-radio show and podcast using the player below. You can subscribe to all future editions on Apple Podcasts (iTunes) or Spotify (and browse my archive of podcasts here).

seed shopping with Jennifer jewell

seed shopping with Jennifer jewell

Margaret Roach: You’re there in Northern California, and I’m here in upper New York State-ish, mid-New York State-ish. So we’re opposite ends of the country.

Jennifer Jewell: But in the same season, right? The seed season.

Margaret: Exactly. “What We Sow,” your book—I don’t remember what month it even came out, but it’s not long ago, really; not that long ago.

Jennifer: Yeah. No, September.

Margaret: I mentioned in the introduction that I’d invited a similarly seed-obsessed friend to the show today [laughter]. That would be you. And I wonder how, if you remember, how you got keenly interested in seed. Beyond the obvious fact that you and I are both gardeners, but what happened? Do you remember what pushed the button for you to go really into seed?

Jennifer: Well, I went really deeply into seed as an adult, when I first moved to Northern California. And it was kind of this… I thought I was moving to a similar climate as Central Colorado. I didn’t really understand how different it was going to be, Margaret. I didn’t understand how different the plants were, how different the climate was. And as a gardener, I failed miserably that first year. I just thought, “I’ll plant the same things I planted in Colorado.” Like it’s drought-friendly, it’s coldish, it’s warmish, it’s dryish. I should be fine. But the difference in the characteristics of the wet, of the dry, of the cold, just threw me for a loop.

At the same time, the native plant biodiversity of California just blew my mind. And I’m in Northern interior California, which is a specific plant palette of its own, and I was blown away. It was like learning a foreign language or being in a foreign country, and you know how like all of your senses are just on alert all the time, seeing things you’re not accustomed to. And so that really sent me down a rabbit hole, if you will, of what were the plants, what did their seeds look like? Because I moved here in a season of seediness. And so they were really apparent all the time, that first few months of me living here. So that was really a big… I was 35 I think when I moved here, I think, so this was an adult falling-in-love story, not a young gardener falling-in-love story, but it was equally love at first sight. [Below, oaks in the nearby canyons to Jennifer’s California home.]

And it was like this panic took hold; not just the panic that we all had, but the panic of, “We’re going to get home and we’re not going to have any seed to grow anything.” So I think it was during that first part of the pandemic sort of lockdown period that you started writing this book. Did that all kind of connect? Is that what got you started on “What We Sow”? And tell us just the short version of “What We Sow” is about.

Jennifer: Well, that was the impetus, right there, was this moment of, and I think a lot of gardeners, you experienced it, many of us experienced it, where we went to place our orders. And again, we were kind of late, because all of a sudden we had a season that we weren’t supposed to be home in the garden handed back to us. And so we thought, “Well, we should probably order seeds,” which is something we do every year, even though we might have some leftovers from the year before or even the year before that.

And when I got out of order, back order, not available, I was like, whoa, this is weird. And when I started doing a little more research into what was happening, I realized just how much I didn’t know about our seed supply.

I have my five to 10 favorite catalogs that come. I look through them, I dog-ear them, and I make a small amount of order in the spring and then in the summer, or in the winter for the spring, and then in the summer for that late summer, early fall planting.

And that’s what set me on the path of writing “What We Sow,” which is, in essence, a gardener’s primer on the state of seed in our world and all the different kind of adjacent fields of interest, whether it’s seed banks, or seed libraries, or seed consolidation, or seed degradation, or biodiversity loss, or the seed renaissance, the small seed-growing renaissance, the seed protection and advocacy by peoples of culture around the globe. All of these things kind of came to play.

And like things I had never thought of, like why do we have all of this information on the seed packets? And why is it the law? And how did that come to be? It was fascinating to write about, and it’s an overview from a gardener’s perspective, not a research scientist, not a seed scientist, but a gardener who was very interested.

Margaret: Before we even get to some virtual shopping [laughter]–

Jennifer: I have my list, I have my list.

Margaret: I know—confess some of the things we’re on the lookout for and so forth, and that we always grow, and that kind of stuff. I know we each apply sort of a filter to which catalogs, and you just mentioned there might be five to 10 that you dog-ear, and so forth.

So what are some of the qualifications to be one of your dog-eared catalogs [laughter]? What does a catalog have to be? Because I know neither of us patronizes the big brands, the kinds that show up in the mailbox of millions of people, whether you request a copy or not, which shall remain unnamed. And they serve their purpose, because they get a lot of people into gardening, because they do that mass-promoting marketing. But you and I are in like another place. And so what are some of the qualifications to be on your list?

Jennifer: Well, especially after doing the research and writing “What We Sow,” where one of the threads is all about consolidation of control [of the seed market globally to a few large pharmaceutical and chemical corporations], which often results in contraction of what’s on offer and sometimes compromise of how it’s being offered. I really am going more and more as I age for the small independent growers and seed sellers who are within my region, more or less. So I really want to support those seed sellers and seed growers who were able to supply us with seed even in the face of a global pandemic and a global supply shutdown. That is one of the criteria.

Because of our growing and certainly longstanding concerns about biodiversity loss, climate change, and ecological warfare being conducted on our planet, I want all of my seed to be either naturally or organically grown. Whether it’s organically certified or not, is less important to me than whether or not they are living the intention of ecological respect and integrity.

Then the final thing is that I want to know that some major proportion of the seeds they are growing and selling are open-pollinated and heirloom. The heirloom maybe is a little bit less, but it’s definitely one of the ones that I note, like, yeah, I want to be a person that buys that seed and helps keep it in the supply chain. And I want to feel like my order matters to these companies, that I am helping this ground-level advocacy and activism in many ways, Margaret, keep going.

Margaret: Yes. And this is the basis of life. I mean, even if you eat meat, the animals are mostly herbivorous [laughter] and they eat something that came from a seed. Do you know what I mean? And a chicken forages. So whatever you eat and that you thrive and survive on, a lot of it goes back to the seed. And of course, all of it goes back to the soil, but it goes back to the seed in most plants that we rely on. So it’s very big.

Jennifer: It’s big.

Margaret: I’m the same way. I want to shop organic or the equivalent. Again, I don’t care if they do the certification as long as they don’t use the chemicals and they follow ethical practices and so forth.

I really like companies that tell me where their seed came from.

Jennifer: Yes!

Margaret: Either they grow it themselves on their own farm, or some of it themselves on their own farm, or they say, “We’re so proud we got seed from this person and this person and this person and, here, meet these wonderful seed farmers that we work with.” I love that, as opposed to this goodness knows where in the world it came from, someplace that was a desert probably, where it’s easier to grow seed, less fungal diseases of something like that [laughter], or I don’t know what, that is nothing like my backyard. Do you know what I mean? Regionally. So regional is important.

I also love that the small guys tend to have, like we all do, obsessions, and they tend to almost adopt particular crops and nurture them. Do you know what I mean?

Jennifer: Yes [laughter].

So I love those specialists like Frank Morton of Wild Garden Seed and all his, I mean, what’s he got, like more than 125 kinds of lettuce that he’s bred [laughter]? These are the people who have changed our salad bowl and our plate, our dinner plate, and our-

Jennifer: For the better, changed it for the better.

Margaret: Totally. [Above, Wild Garden Seed’s ‘Fawn’ lettuce.]

Jennifer: Because there’s a ton of lettuce out there you don’t necessarily want in your salad bowl, also.

Margaret: Yeah, or I don’t know if you know Glenn Drowns at Sand Hill Preservation Center.

Jennifer: Yes.

Margaret: Been at it for a long time, and I mean he has more than 150 kinds of winter squash and a couple of hundred kinds of sweet potatoes. These are collections, lifelong collections, a passion, of genetic material that would otherwise be lost forever. So that’s what turns me on, is those types of people.

Jennifer: And that history, and that stewarding. It grows the best of humanity as well as the best of the food for humanity, And it’s art; there’s this artistry to that length of research and relationship that has led to these collections. It gives me the shivers, actually.

Margaret: Yes, it does. It does. It does. Because it’s not like collecting “stuff,” like things, inanimate things.

Jennifer: No.

Margaret: No, it’s stewardship. It really is. It’s a relationship. It’s intimate. So you’re Western, and you said you go regional where you can. So what are some Western… and I’ve gathered some names from the Southeast, where I occasionally dabble in purchasing some seed, too [laughter], even though I’m in the Northeast. So what are some of the places that you go to, and why?

Jennifer: It is so interesting, because I get catalogs from everywhere, and they’re the ones on the East Coast that I’m just like, “Oh, I want to try that and that.” When I get my emails from Hudson Valley Seed or Southern Exposure, I’m like, “Ooh!” But by and large, I try and stick to my Western ones, and again, I go a little bit out of my exact region.

And at this point, my most local is called Redwood Seeds. It’s a small company founded by a couple. They’re probably about two hours north of me, and they’re just doing a fantastic job. So that’s the first one.

The next one is called Living Seed Company, and it is over on the coast. So the coast is really, really different, but sometimes they have seeds that I can’t find from Redwood Seeds, which is on the interior, so much drier.

And Territorial Seed is up in Oregon. They have a fantastic big selection, and they have a wonderful history of advocacy and education.

Renee’s Garden Seeds is down in Southern California, or its headquarters is, or I guess it’s Central California, but it’s way south of me. They’re probably the biggest catalog [on my list]. She’s very consistent, very reliable, and I love the work she’s done for the industry as a woman leader in this field.

The two that are sort of outside of my range when I’m talking about vegetable seeds is High Desert Seed, which was a favorite of mine when I lived in Colorado. And this woman-owned company is out of, let me get this right, the western slope of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the town of Paonia, which interestingly, I grew up going to at a family cabin that my mother and father bought while my father was doing his PhD research in Paonia.

They have some really interesting high-elevation seed research and trials and selections, and they have a wonderful… Going back to your statement about how we love companies that actually give credit and uplift the growers who are in their collaboratives, they have the most wonderful stories of where their seed came from and who their growers are. So I love that page.

Then the next one…I have three more: One is the Native Seeds/SEARCH group out of the Tucson area. Really interesting native and indigenous heritage seeds, a lot that go only to the indigenous communities there, but then many that are available to the public, as well. And just so much research and advocacy and kind of capacity-building in their seed-growing network for the benefit of these indigenous communities through indigenous leadership. So I love their work.

And I love toying with native seeds, Margaret. I love collecting them, and I love looking for them. And the two that are my go-tos are Seedhunt, which is out of Southern California, but she collects all over the state. And this is another woman-owned endeavor by Ginny Hunt, and she just has some fantastic selections. I’m a big-

Margaret: Of native plant seeds for native plants.

Jennifer: Some non-natives, as well, like interesting, hard-to-find non-natives, but a lot of really good natives like excellent buckwheats, Eriogonum, and Clarkia. Fantastic.

And then Theodore Payne Foundation in LA has some great native-plant seeds. I know you did that great piece on the Northwest Meadowscapes, another great one. But again, just a little far north and damper than me. That’s like my next level.

Margaret: And he is spreading. It’s a couple who owns that seed company, and they’re widening the area that they’re serving, and so forth.

Jennifer: Local areas, yeah.

Margaret: It’s interesting, because you are in Northern California. Parts of Northern California, parts of Oregon and Washington, a lot of prime seed-growing land in this country is traditionally-

Jennifer: Yeah, oh yeah.

Margaret: Because of the pattern of when the rainfalls do and don’t come. You don’t want at seed-harvest time, you don’t want it to be pouring all the time. And traditionally, that was an advantage in these areas, and there’s lots of other reasons, but I’m oversimplifying [laughter]. But anyway, so there’s a lot of seed companies. I mean, there’s other ones in your wider region, for instance, Siskiyou Seeds.

Jennifer: Oh, Siskiyou Seeds, excellent.

Margaret: Don Tipping’s got like 700 different kinds of edibles and flowers and herbs and whatever. And Peace Seedlings.

Jennifer: Peace Seeds. So good. I saw, let’s see, I think High Desert Seed and Redwood Seed both attributed Alan Kapuler [the Peace Seed founder] with many of their seed selections.

Margaret: Exactly. Exactly.

Jennifer: Yeah, which is great. They’re excellent. And Hume Seeds is another one up there. You’re right. And just north of me, that jump over the border makes a huge difference in their capacity to grow seed at really big scale.

On the other hand, if I wanted collards, who has more than a dozen? Well, Southern Exposure Seed Exchange [laughter], and if I wanted to try collards—do you know what I mean? If I wanted to have fun with it, it’s not going to be-

Jennifer: Thank you, Ira Wallace, and the Heirloom Collard Project.

Margaret: It’s not going to be my main crop, but, yeah, so lots of… And you mentioned your most local ones, and my most local ones are Hudson Valley Seed, which you did mention. And Turtle Tree Seed, which is biodynamic, which is right near me, as well. So yeah, there’s something to shopping local, right? [Laughter.]

Jennifer: And then, as we know, one of the issues which you’ve already kind of touched on, is that you can grow seed really well in other areas, but it’s then not necessarily adapted if you want to save seed and grow it on and on and on. So these growers are doing some of the adapting for us if they are growing them in our area. And then we know the seed is resistant to when we do have damp, when we do have drought, when we do have cold spells. And that’s an interesting balance, right, between getting seed that’s going to be great this year, but may not be well adapted over time, versus seed that might be really well-adapted over time but may not have the exact, I don’t know, greatness the very first year. I don’t know.

Margaret: Yeah. And that’s the same reason—the fact that seed is alive and that over the generations it will adapt to the conditions that it’s grown in. In subtle ways, it will change, it will evolve to adapt to the conditions. And that’s the same reason I want seed that’s grown organically. Because I don’t want seed that expects me to intervene, and I say “expects,” anthropomorphizing the seed, but that expects me to intervene if something’s going wrong, and nuke it.

Now speaking of nuking it, one of the most chilling things in the book is how we’ve poisoned seed. We’ve done a lot of bad things to seed. We’ve made it disappear; so many varieties have disappeared because we’ve turned it into intellectual property that you can patent and all these kinds of crazy things, but we’ve also poisoned it. So just tell us about that and about that’s another reason to buy organic seed, I think.

Jennifer: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. Because you are voting with your dollar and your economic power for a world that does not poison the heck out of everything. The rate at which our seed, our commodity level seed, is being pretreated with, whether it’s Roundup Ready Toolkit or it’s the insecticides and neonicotinoids, I believe the EPA now says that every bit of non-organic corn, and there are millions of acres planted out in corn in the U.S. today, all of it that is not organic is now treated with either herbicides or herbicide resistant and/or neonicotinoids.

That goes directly not just into the plant, which then is the food, which is then the pollen, which then contaminates the non-treated seed and corn pollen within many, many miles, like the reach of the wind-pollinated corn pollen is phenomenal. But it’s also leeching into our soils, into our ground and surface waters, and it contaminates all the lives that are supposed to make their lives there. It’s astronomical.

And we keep pounding away at this, and we think that it’s, “Oh, we should ban Roundup,” right? But sadly, you can ban DDT, thank you, Rachel Carson, and you can maybe ban Roundup, but there are 18 to 20 chemicals on the market, or being readied for the market, right behind Roundup, so that our use of pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, biocides, which is Rachel Carson’s word for them-

Margaret: Kill everything, right?

Jennifer: …is increasing, not decreasing. And it’s connected to so many of the health issues in our environment and in our lives, in our own bodies and lives. We just have to say let’s try it without this. Let’s go back to figuring out ways to not use chemicals. They should be, in my opinion, regulated like weapons, or better than we regulate weapons. That’s how strong they are.

Margaret: We’ve run out of time, of course, but that “vote with your seed dollars” is what we’re saying. Vote for a safer environment with your seed dollars by giving them to companies that don’t do that, don’t treat the seed.

Well, Jennifer, you and I could talk forever and ever, because too similarly, as I said, seed-obsessed people [laughter]. But thank you for sharing some of your source. Thank you for making time today.

Jennifer: Oh, thank you very much. And happy seed shopping this season.

enter to win a copy of what we sow’

I’LL BUY A COPY of “What We Sow” by Jennifer Jewell for one lucky reader. All you have to do to enter is answer this question in the comments box below:

Any catalogs to recommend (and tell us why)?

No answer, or feeling shy? Just say something like “count me in” and I will, but a reply is even better. I’ll select a random winner after entries close Tuesday December 26, 2023 at midnight. Good luck to all.

(Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.)

prefer the podcast version of the show?

[ad_2]

seed shopping with Jennifer jewell

seed shopping with Jennifer jewell