Three Little Pigs story reinforces prejudices that biomaterials are “terrible”

[ad_1]

The fable of the Three Little Pigs highlights negative perceptions about natural construction materials, according to James Drinkwater, head of Built Environment at philanthropic climate organisation the Laudes Foundation.

Speaking about the need to increase the use of timber and other biomaterials in construction, Drinkwater said that the well-known children’s story presented natural materials such as straw and wood as “terrible”.

“There’s a classic story in England called the Three Little Pigs,” Drinkwater said during a talk hosted by Dezeen. “The first [pig] made its house of straw and that natural material was terrible.”

“There’s a need to change perceptions to show what’s possible, and to amplify those narratives.”

People view natural construction materials as weak

The Three Little Pigs story refers to a fable that dates back to the 1800s, which tells the tale of three pigs who build houses out of straw, sticks and bricks respectively. While the Big Bad Wolf blows down the two pigs’ houses made of natural materials and eats their occupants, the brick house prevails and the third pig is saved.

Drinkwater referred to the fable in order to highlight how people often view natural construction materials as weak during his discussion of a new network called Built by Nature, when in fact building with natural materials could significantly reduce climate change, according to Drinkwater.

“The built environment represents nearly 40 per cent of all carbon emissions. So it’s a big part of the opportunity for climate mitigation,” warned Drinkwater.

Established by the Laudes Foundation – a philanthropic organisation that has a dual focus on climate change and social inequality – Built by Nature is a network and grant-making fund on a mission to normalise and accelerate building with timber in Europe.

Mass timber is increasingly replacing carbon-intensive materials

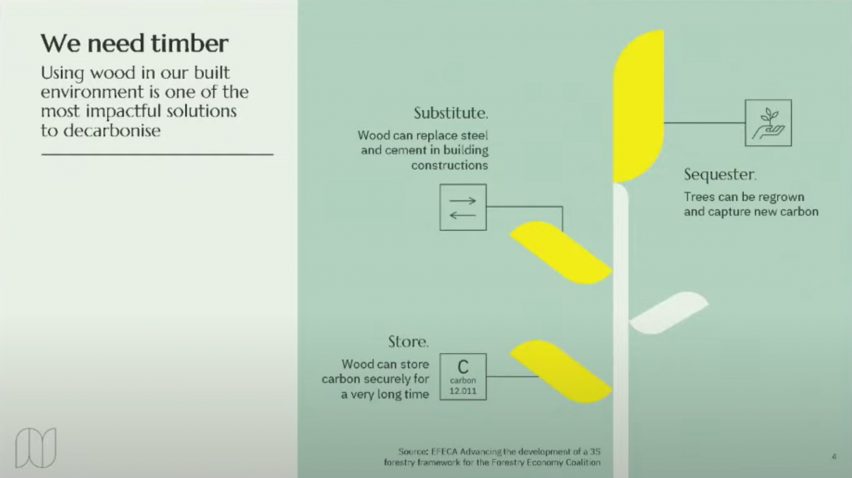

The network’s long-term aim is to achieve a net-zero built environment where embodied carbon is radically reduced and safely stored within mass timber architecture.

Mass timber encompasses various types of engineered wood that are increasingly replacing carbon-intensive traditional construction materials such as concrete and steel.

“Built by Nature encompasses the theme of how do we move beyond ‘extractive’ to ‘regenerative’ in our build environment,” added Drinkwater.

“What does it mean to get this right for forests and create a climate-smart forest economy so that when we are sourcing timber, we’re making sure we’re improving the sequestration capacity of forests as a sector procuring from those forests?”

“We need to make sure we’re doing that in the right way and creating those demand incentives to drive reforestation.”

During the talk, Drinkwater also discussed the need for a circular economy within architecture, which is an economic system where waste is minimised through continuously recycling materials as much as possible.

“We can’t simply switch everything and kind of ask nature to provide us with all of the solution. So we need to be very joined up across sectors,” he acknowledged, calling for applicants to Built by Nature’s Accelerator Fund.

“Our [current] average building life of 42 years is nowhere near enough. We need to be designing these buildings and timber beams and whatnot for their second and third life,” he added.

“As those trees sequester carbon during their life, and then we start to put them into our buildings and our cities, it’s really critical that we’re storing that carbon safely for a very long time,” he explained.

“But the science demands that we don’t just reduce emissions. We’ve got to remove a hell of a lot of this stuff from the atmosphere.”

“And arguably if we created 40 per cent of the climate issue, we really now need to work with nature, which is our strongest tool to get on that negative emissions track. We know the science says that forests offer our best hope,” continued Drinkwater.

Hosted by Dezeen founder and editor-in-chief Marcus Fairs in collaboration with window and skylight brand Velux, the talk explored ideas about how architecture can work with rather than against environmental systems in order to support sustainable development.

Also part of the panel discussion was Kasper Guldager, co-founder of European real estate company Home.Earth, and Susanne Brorson of architecture practice Studio Susanne Brorson.

“There are matters that the built environment really needs to react to and address,” said Guldager, referring to the relationship between architecture, social inequality and climate change.

“We have this dual focus on social inequality [and climate change] – like today, we see that real estate is separating people. People who can and people who cannot afford things. And we see that real estate is driving climate change and that our planet cannot sustain the way we build.”

Brorson also expressed her determination for the built environment to be constructed in line with nature.

“I’m trying to bring the next generation of architects closer to this idea of specific [architectural] solutions for certain climates and environments,” she said.

The main image is of CiAsa Aqua Bad Cortina by Pedevilla Architects, an Alpine house in Italy that is clad in shingles made from trees that fell during a storm.

[ad_2]