reading the land (with the help of trees), with noah charney

[ad_1]

A new book I’ve been reading called “These Trees Tell A Story: The Art of Reading Landscapes” (affiliate link) takes the reader along on explorations through a diversity of places looking for hints on how to know the island as its author, Noah Charney suggests.

Noah is an assistant professor of conservation biology at the University of Maine and co-author with Charley Eiseman of the award-winning field guide “Tracks & Sign of Insects & Other Invertebrates,” one of my much-used favorites.

On the website of the publisher of Noah’s latest book, Yale University Press, it describes it as, “deeply personal masterclass on how to read a natural landscape and unravel the clues to its unique ecological history.”

Plus: Comment in the box near the bottom of the page for a chance to win the new book.

Read along as you listen to the June 19, 2023 edition of my public-radio show and podcast using the player below. You can subscribe to all future editions on Apple Podcasts (iTunes) or Spotify or Stitcher (and browse my archive of podcasts here).

reading your landscape, with noah charney

Margaret Roach: Hi, Noah. So you taught a course I think that the idea of this book kind of derives from a course that was called, I believe, “Field Naturalist.” Is that correct?

Noah Charney: Yeah, that’s right. And in that course every week we’d go out to different sites on the landscape and we’d take the van to some spot that the students really wouldn’t know where they’re going and they’d encounter a mystery, like the trees would change on one side of the line to the other or something. There would be some pattern that then the students would have to discover what was driving that pattern, what caused it, and they’d just have a few hours or the rest of the day to uncover all the forces that came to tell the story of that site.

Margaret: It’s fun, kind of, the forensics. I should say I know your collaborator on your previous book, the field guide, Charley Eiseman. I know you two have taught animal tracking and all kinds of other things over the years as well. So you’re very astute observers. But I didn’t know until this book that you were an astute observer of this much larger level.

I mean, I guess I should have inferred that, but you know what I mean? I knew more about that you knew what kind of spider made what kind of web [laughter] and what kind of cocoon and animal track and things like that.

Noah: Honestly, neither of us really knew anything about insects or much about insects and invertebrates before we wrote that book. We were studying animal tracking and we realized that no one had written one about the insects and invertebrates so we took a deep dive into that. And Charley now as you probably know has gone really far into leaf miners and galls and knows a lot more about that. But neither of us started out on that path. We’re just sort of curious and naturalists, generalist naturalists.

I mean, Charley went through the field naturalist program at UVM, which was the basis for the course that I taught, too. And so very much generally trained and interested.

Margaret: Right. So curious is a good word. And early in the new book you tell an anecdote about hiking with a friend, I think it was near Boston, and you eventually come to what I think is referred to as a greenway, sort of a bike path with narrow strips of green alongside. You describe this as an “invasive-dominated, degraded ecosystem.” [Laughter.] But then you walk a while longer and you notice some particular trees and you close your eyes. So tell us, in that kind of a situation, what do you see with your eyes open and what do you see with your eyes closed? What goes on in a moment like that for you?

And I closed my eyes and I think back to those species are floodplain trees and live in very wet soils. And that probably was a riparian wetland there before it became a bike path. Closing my eyes and picturing and hearing the wood frogs and spotted salamanders breeding in that wetland there before it was turned into this bike path with all the kids and their strollers and such, and seeing that echoes of that ecosystem are still there. The soils beneath that bike path are still sort of created in the way that would facilitate those sorts of species.

Margaret: So as gardeners, when someone says, “What kind of soil do you have?” we are frequently talking about what we’ve almost “made” in our raised beds or something. It’s not… “What kind of soil do you have?” takes another level of meaning in the kind of explorations you’re talking about in this book. It’s really ancient and underlying and so forth. The thing that defined the place over a long period of history, yes?

Noah: Yeah. And the way I see it, too, it helps us maybe move away from good versus bad soil, but it’s like what is this soil? Maybe it isn’t perfect for the plant you had in mind for growing, but it tells a story of all that’s important about that place and all the plants that would’ve grown there naturally, and the things that it’s very good for something, and it came from a particular came a set of circumstances and there’s a story behind how that stuff came to be there.

Margaret: Are there places that we… So speaking of soil, the topography of a place, are there references, are there places where we go look, that we can get some of this old information, or are there surveys and are there… Just so that I know what references to recommend to people.

Noah: I mean, it depends on which layer you’re talking about. So at the larger scale, of course, there’s the USGS surficial geology maps or bedrock geology, both of those, like the official geology maps for your local… I was just looking at New York State has some published and you’ll see what are the glacial land forms and at a coarser resolution, your neighborhood kind of area, what’s created the soils. But then at a very local, like this side of the hill versus this side, are very small-scale like that bike path.

I mean, those aren’t necessarily going to be mapped on the geologic surveys, but you might have topographic surveys and stuff. And there may be some natural-communities inventories that might map some of those things. But at that scale, it’s more about knowing the trees and knowing the plants and knowing how land forms create micro little ecosystems.

Noah: Well, I mean there’s… The biggest influence of slope or one of them is the angle, the aspect, which direction it’s facing. Is it facing south or is it facing north? And that has a big impact on the soils, as folks know. In the Northern Hemisphere, the sun is always in the southern part of the sky, so those south-facing slopes tend to dry out and be really hot. And the north-facing slopes are cooler and moister and create different conditions for different sets of species.

The slope itself creates drainages, and up higher on the slope you have less soil buildup. It tends to be an erosional zone. And then down at the bottom is where there’s a depositional zone. So you have more layers of soils and more towards the wetland soils more frequently down at the lower slopes. So there’s a lot of different elements that go into that.

Margaret: Right. And again, I’ve lived downhill for a long time and I don’t really think about it. I think about what… And I’m a layperson, but I think about what I call air drainage. I think about the fact that the town that we call “the flats” below me get colder in prolonged cold moments, like overnight and so forth, than I do because I think that air drains up over where I am or something. That’s my very, again, amateurish interpretation [laughter]. But I think about that, but I hadn’t really thought about the drainage area and then also like you said, what’s deposited that there’s less soil up there and more soil down below, and generally speaking and so forth.

Noah: It’s very context and site-specific, too. I mean, my house where I spent most of my time in Western Massachusetts, we live right on the shore of the glacial lake deposit. So 10,000 years ago, there was a glacial lake there, and down below in our yard, essentially lake bottom sediments. We walk up the hill and we get above lake level, and suddenly it’s glacial till and that change is really dramatic. There’s no rocks in our yard, but there’s lots of rocks up and above us.

Margaret: And that’s where I am. My neighbors all say, “Well, how do you grow all those plants? You have such rocky soil.” And I’m like, “No, the rocks didn’t land here.” [Laughter.] And yet they have them.

The book has the word trees, “These Trees Tell A Story” is the title. So you look at things when you come to a place, you look at things like whether the canopy trees and the understory trees are the same or different, for instance. Tell me a little bit about that, because that’s another interesting thing that I hadn’t really thought about being a closer observer of, and that’s silly, but I hadn’t.

So there are these, over centuries, these sort of waves of different species that come through as a forest develops. So when you walk into a forest and you see the canopy is all white pines and the understory is all, say, red oaks, that if you pause for a second and think about what will happen in 100 years when those white pines die, it’ll be a canopy of red oaks. So that tells you that the forest is still in transition, and it tells you something about the past of that forest and something about where it’s going in the future. [Above, a red pine forest with hardwood understory.]

Margaret: In the start of the book, you tell the story of a couple. You take us in each chapter through to a different place, like I guess you took your class to a different place to solve mysteries every week. In the start of the book, you tell about this couple you know who are considering cutting down a bunch of trees in their yard for various reasons. They need more light, they want to have an orchard, and they need to install a drainage ditch because at least one of the trees is rooted where there’s persistent water, and the wet soil is damaging to the foundation of the house and so on.

But you talk to them about it. You get in a conversation with them about it, and you say… I’m going to quote in the book you say: “The pines, the oaks, the mud, the water, the land, it’s not random, but all part of a long unfolding story that you have a role in. Dig up the details,” you tell them, and then you suggest they look both into the past and into the future for details. So is that the exercise roughly?

Noah: Yeah. That is it. And for them, and before they start to fight their soils and just come in with their vision of what they wanted in their yard absent having… Before they’d even bought that house, start by looking at the landscape, looking at the canvas that they’re now living on, and really understanding it.

So that maybe the hope is that instead of fighting against it, we can find ways to work with it. Because understanding where it comes from, the long glacial history, and then as you manipulate your landscape, you’re going to be affecting it. You’re going to be affecting your neighborhood, and all the species that come to visit. So what is the context? What species are around and what might take refuge here or in your neighbor’s property?

Margaret: Right, because you talk about “the ripple effect” that each action we take has throughout the whole ecosystem, not just our property line, but way beyond that, that ripple effect.

Noah: Yeah. I have a nonprofit that I run down in Nashville, and a lot of people are so focused on their parcels and laws, and policy, and everything is focused on parcel by parcel, and “our house” by lot by lot. But really the species, the ecosystems, they’re not worried about these property lines and trying to work beyond those and work on regional area, that planning is really important.

Margaret: I guess it was probably Doug Tallamy at University of Delaware who told me the expression “conservation corridors,” that we’re all connected and these contiguous areas and so forth. It makes a corridor potentially for conservation efforts or to… Yeah.

One interesting thing is that in… And I don’t remember which chapter it’s in, but you also seem to express some nostalgia in a way or whatever for the thickets or hedgerows of what we all term invasives. Things like multiflora rose or bittersweet, oriental bittersweet; things that we see along the roadsides or maybe even have at the fringe of our own garden and things you call “messy invasive thickets.”

Yet, you also seem a little conflicted about just trying to beat them back and erase them as is the mandate these days. Can you just talk about that? When we’re looking at the “now” of a place, which frequently in a lot of the country because of all the disturbances in our history of our nation, well, every nation, has been changed, has been greatly changed, and is frequently a mix of native and non-native. And sometimes the non-natives have the upper hand.

Noah: I’m definitely conflicted. I have different minds on the different parts may think different things. And I will say in the broader discipline of ecology and conservation biology, there’s a recognition that there is no part of the world that is untouched by people. There isn’t like nature absent humans. And the future is going to be more and more impacted by global climate change and all sorts of things. So the future ecosystems that are going to be on this planet are probably a lot of novel ecosystems.

Ecosystems that have never existed in the past. And instead of the sort of our knee-jerk nostalgic historic way of conserving, which is just keep the things as they always have been in nature, recognizing that things are changing and things are going to change. And we need to view every little plot of land, whatever species happen to be there as those are the species that are there and they have certain values. They perform ecosystem services no matter where they came from.

And in the case of the multiflora rose thicket, I think you’re referring to the last chapter when I’m talking about this orchard, which is this invasive thicket that we might all want to just cut down because there’s no natives there. But at the same time, it’s providing habitat for bobcats [above] and fishers and all sorts of predators that we have some interest in protecting.

So there are values associated with any ecosystem. It’s doing things. It’s part of the flow of nature and we can use species for certain purposes and maybe natives are… They do support more bugs. They do feed more chickadees; studies have shown this. But the non-natives also can play a role, and just mowing them down as a knee-jerk reaction may not always be the right choice. And it all comes from our values and what we want to see around us.

Margaret: And what we probably also really… If we sit and really think about it, what’s going to happen next? Is there going to be stewardship, or are they all just going to come back. There’s a lot of next steps in those decisions.

Noah: Right. What are we replacing it with?

Margaret: Right. So you said you’re in Western Massachusetts when you’re not up at school in Maine teaching. What is your home property? What’s its history and hydrology? What kind of place is it? Tell us a little bit more about it.

Noah: Yeah. As I mentioned before, it’s set in into this hill slope that the house itself is below glacial lake level, from Glacial Lake Hitchcock 10 thousand years ago. And above it is all sort of glacial till. It’s a unique little mountain that has some old growth and some hemlock forest, some of which are getting attacked by woolly adelgid. And then the yard itself though is historically it was a cornfield before we moved in, long before. And so the soil has been tilled, but it’s really nice, soft soil because of the glacial history.

So it’s right on the edge of a forest, and the forest is second-generation of succession, although further up there’s older succession forest. But yeah, I don’t know.

Margaret: So you write in the book about something I’d never heard the expression before, but I kind of understood it, living in a rural place with boundaries between large-ish properties and so forth: You talk about witness trees. Tell us what a witness tree is, and do you have any witness trees at your place?

Noah: I haven’t actually worked myself with witness trees. It’s something that at Harvard Forest, the folks there did a lot of research with, and folks continue to work on. But essentially back in the day when they were doing land surveys, the property corner is, when you would do a survey at the corner, there would be a tree. What is the nearest large tree? And that would be witness to the document of the property boundary. And that would be written down in the deed, and those trees would typically be left, and they would be big old trees. And the species was recorded in those deeds. So we have a record going way back of something about the forest in place over time.

Margaret: It’s pretty amazing. I mean, now they put a pin in, right [laughter]? They put a metal pin in or just use a GPS or whatever that’s called.

Noah: And they may still put some rocks and things in, too. I’m not deep in the literature. I’ve heard people talk about this and write about it, but they would still record the nearest species.

Noah: So typically if an oak tree was to sprout from an acorn, it would grow up one stem and it would turn into one single-stem tree. But if you cut that tree down, then it’ll grow stump sprouts from the edges, and those will grow up and turn into trees themselves. So often when you see trees that are multi-stem like that either two, three or even more, that often suggests that the above-ground portion was killed. And in a lot of cases, you can tell that it was logging. If they’re a whole bunch, and they’re all the same age, and you can actually see the distance between those trunks, between the current trunks would be the edges of the old trunk, if that makes sense.

Margaret: Right.

Noah: Because the sprouts would come up at the edges. So you can see a logging history. I think there’s a picture in the book of a slope that was all cut. It was all these oaks that I think maybe 100 years ago were cut and re-sprouted. Not all trees do that. And there are other things that could kill that above-ground leader, but often that’s what it is.

Margaret: Yeah. I mean, it was just a fun one because it’s, again, this sort of forensic bit of history. It’s this indicator, but we could walk past it in a certain place and not know what it was.

Noah: It’s really common, too.

Margaret: Yeah, and that’s what you said.

Noah: I mean, I’m sort of child-minded in this whole thing, and I tend to have these very simple things that I know and I look for. I go into forest and I’m like, “O.K., is the understory the same species as the canopy? Are there lots of split-trunk trees around that look like there were the logging event?” And then I’m like, “O.K., yes or no.” And this tells me whether it seems like it was logged or it’s sort of in successional stages still, or whether it seems more as an older forest. There’s just a few of these very simple things that I tend to look at that are over and over again, I see. [Above, a tulip poplar forest with beech understory.]

Margaret: Yeah. You talked about slope and there’s the issue of elevation, which I was talking about and so forth. I have friends who are expert birders. They come at it from a different perspective. They’re reading the land in a different way, in a way, because I have one friend who I said something about having grouse, and she said, “Oh…” And then someone else who was there said, “Oh, I’ve never seen one. I only live a mile down the road.” And she said, the expert woman in the conversation said, “Well, that’s why you said a mile down the road, because you’re not in enough elevation. They don’t really like…” And she knew exactly about the birds of the place and these subtle gradations of difference. Right?

Noah: And with grouse, too, that’s when we’re doing snow tracking with me and Charley. Every time we’re in a white pine understory thicket or some really dense area, we’re like, “O.K., we’re going to find grouse and snowshoe hare here.” It’s like knowing where on the landscape and things are queuing in. And those thickets of white pine are coming from a sort of forest logging history, typically.

Margaret: The animals know how to read the land, don’t they?

Noah: Yeah.

Margaret: [Laughter.] Yeah. And up in the last couple of minutes, up in Maine, you’re getting to… How long have you been at the university there?

Noah: I started remotely from Western Mass mid-pandemic, and then moved up here, I guess last year. So two and a half years or so.

Margaret: O.K. So is it a very different kind of place? Is there something you just want to tell us a little bit about discovering that place?

Noah: I’m still getting to know it. It took me decades to know the landscape of Western Mass, and I was able to teach this course because I’d lived there for 20 years and I knew all these spots. I really could tell the stories. I think it’s so important to know your place and have that deep relationship with the land, like memories of people and animals and things that you’ve done on the landscape. And that’s how you get to understand the world.

For me, I’ve been here two years, and it’s similar species, but I still feel mainly an alien up here [laughter]. I’m sort of getting to know it. I can tell some stories. I have a couple spots, but I don’t feel like I have that deep relationship yet. It’s a different kind of world here.

Margaret: Yeah. It’s beautiful. The book is beautifully written. It’s called “These Trees Tell A Story,” and I’m learning a lot from it. It’s way over my head at the beginning, but I’m starting to grasp. So I love that. It’s making me stretch the way that when I first read yours and Charley’s “Tracks & Sign of Insects & Other Invertebrates” [affiliate link], I had no idea what it was talking about [laughter]. So good. You’ve opened my eyes again. Thank you very much.

Noah: Hey, well, thanks so much.

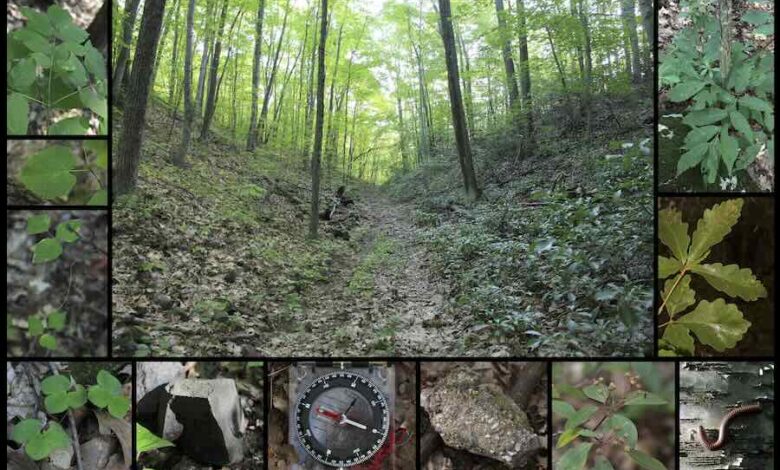

(All photos from “These Trees Tell a Story” and used with permission.)

enter to win a copy of ‘these trees tell a story’

I’LL BUY A COPY of “These Trees Tell A Story: The Art of Reading Landscapes” by Noah Charney for one lucky reader. All you have to do to enter is answer this question in the comments box below:

Do you know anything historical about the land where you live and garden, and what it was before?

No answer, or feeling shy? Just say something like “count me in” and I will, but a reply is even better. I’ll select a random winner after entries close Tuesday June 27, 2023 at midnight. Good luck to all.

(Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.)

prefer the podcast version of the show?

[ad_2]